An Interview with Alanna Fields

January 6, 2021

As both an artist and archivist, Alanna Fields engages the history of the Black queer archive, altering how we interact with photographs from the past by ushering the viewer to get closer and look again. Layering found photographs with acrylic, oil, and wax, among other media, Fields invites us to not only reconsider what we see, but what we know or assume based on what we see.

“I am drawn to subtle and audacious expressions of queerness and amorous connections through gesture, gender presentation and inscriptions on the photographs themselves,” writes Fields. The images Fields excavates and transforms resist stereotypes and offer a glimpse into what Saidiya Hartman refers to as “the beautiful struggle to survive.”

Through negotiation between legibility and masking, Fields examines the dialogue amongst Black queer bodies in the photographic space. Fields is a 2018 Gordon Parks Foundation Scholar, 2020 Light Work AIR, 2020 Baxter St CCNY Workspace AIR, and the recipient of Gallery Aferro's John and Lynn Kearney Fellowship. Fields received her MFA in Photography from Pratt Institute in 2019, and currently lives and works in New York City.

—Jessina Leonard

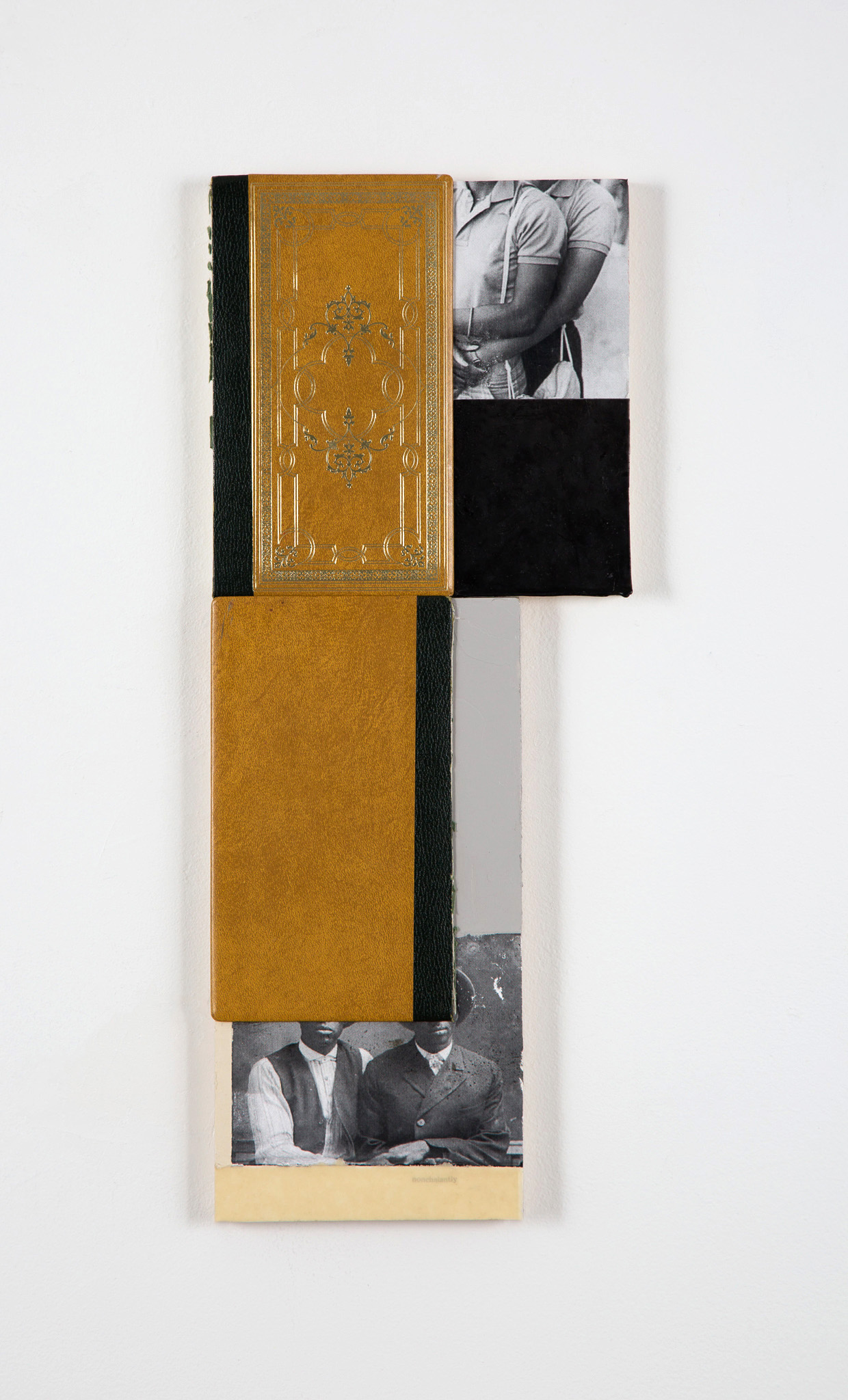

Nonchalantly, 8 in. x 20 in., Digital Inkjet Prints, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, Book, Acrylic, on Panels, 2019

Untitled II, 6 in. x 8 in., Digital Inkjet Print, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, on Panel, 2019

JL: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me, Alanna. While your work is based in photography, you often incorporate other elements: oil, acrylic, wax, archival images and ephemera. How did your interest in photography begin and what led you towards working experimentally with the medium?

AF: My interest and fascination with photography is in its potential to create counter-narratives and expose complex histories. I began working experimentally with photography in a material way with my series As We Were. Beginning this series, I knew the narratives that I wanted to address and counter in the work had layers of complexity around blackness and queerness—and thus I found that these materials, wax in particular, created a visceral language that got to the core of my message.

JL: Where do you find the archival images you work with and what are you looking for? What is your personal encounter with these images like?

AF: I primarily source my archival photographs through online collectors. In searching for these images, I look for various things from cabinet cards, tintypes, and booth photos to military and vernacular photography that center black queer life, couples and individuals. I am drawn to subtle and audacious expressions of queerness and amorous connections through gesture, gender presentation and inscriptions on the photographs themselves. Searching for and finding these photographs is a very intimate process of locating Black queer ancestors and honoring them by bringing their presence and existence to the forefront.

JL: Gesture plays such an important role in how you crop and reconfigure these images, particularly in your series, As We Were. There is the soft parting of a lip, an arm wrapped tenderly around another person’s body, or two figures’ heads resting against each other. I am interested in how your emphasis on these gestures both uncovers and re-narrates the history of Black queer culture. Can you talk more about this?

AF: In As We Were, gesture is a common thread throughout the series as I looked closely and primarily at couples. In these images, there is this quietude of queerness expressed through gesture, subtle touch, and proximity between two bodies that creates amorous language narrating untold love stories. This counters the history we have been offered. The truth in our history is that Black queer people have always existed in both quiet and audaciously unapologetic ways.

Dark Body, 24 in. x 18 in., Digital Inkjet Prints, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, Acrylic, on Panels, 2019

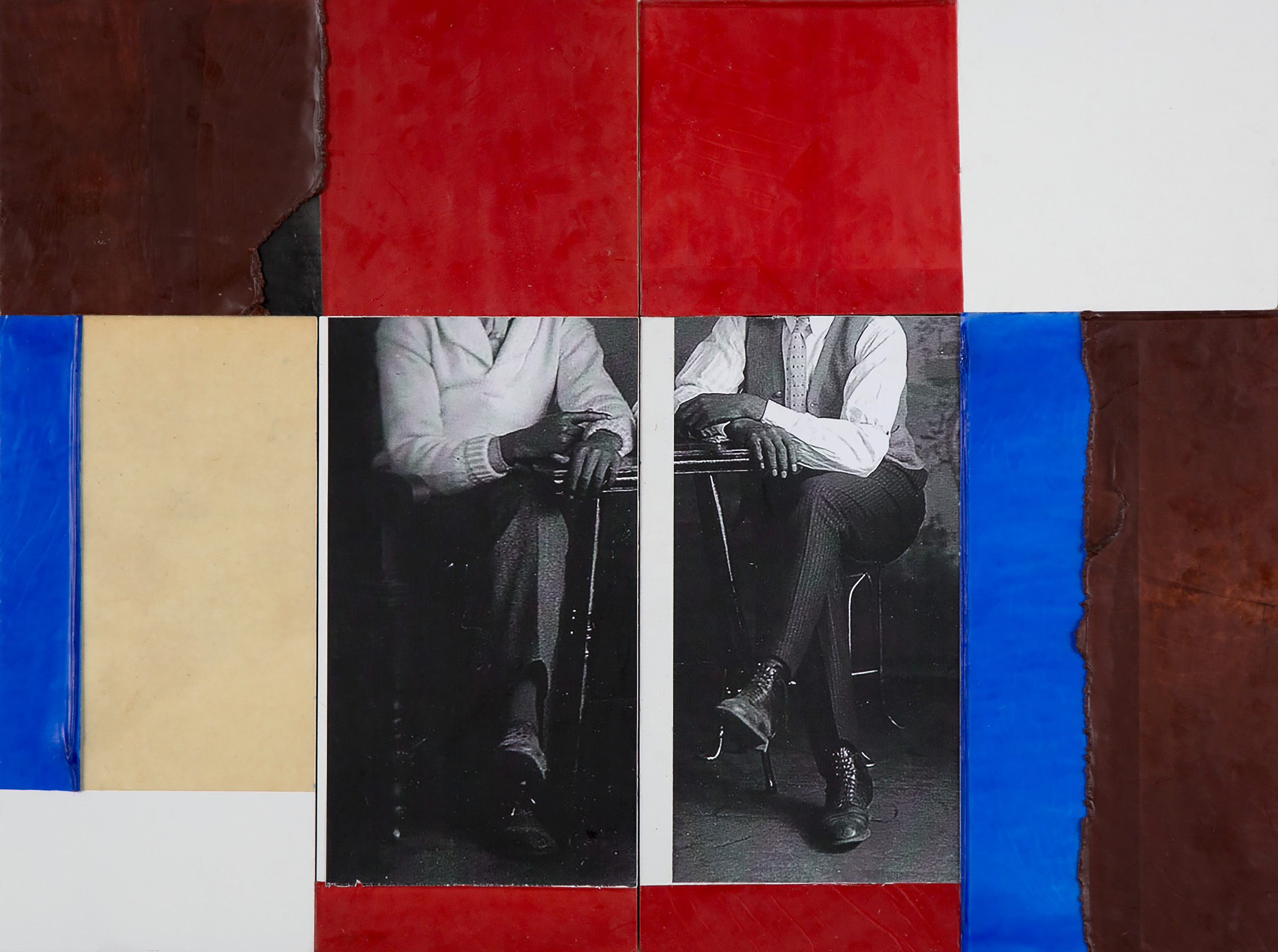

Untitled (Blue), 25 in. x 25 in., Digital Inkjet Print on Canvas, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, Frame, 2019

JL: Deborah Willis talks about how the archive of Black images does not just exist in the past, but is also expanding exponentially in the form of digital culture, through everything from memes to TikTok. However, your work seems specifically focused on a past archive. Why is that important to you?

AF: Looking at the archive of Black queer pasts is inevitably contemporary because these are images we’ve never seen before. It was the lack of early images of Black queer people that I had access to that peaked a curiosity of how we lived prior to now, and outside of our engagement with the social movements that have marked our history. Thinking of early representations of Black queer love, the everyday moments that truly show how a person lived, that show community. There has been such a lack of images and a lack of prioritization of bringing such images to the forefront. The past is always present and the future depends on our engagement with the past.

JL: Looking at your work, I am reminded of many artists who have similarly drawn from Black family archives, such as Lorna Simpson, Leslie Hewitt, and Lorraine O’Grady, among others, in order to reinterpret and recontextualize Black history. How do you place your own work within this canon of artists?

AF: I see my work similarly address the complexities of Black life and identity by revisiting the past as a means to look forward and beyond but to also look deep within a memory. That deep looking pushes to the surface that which has been suppressed, marginalized and thoughtfully quieted. I place my work in a space of excavation, digging up histories that have been discarded as unimportant or buried to hide their existence. Black queer history is Black history.

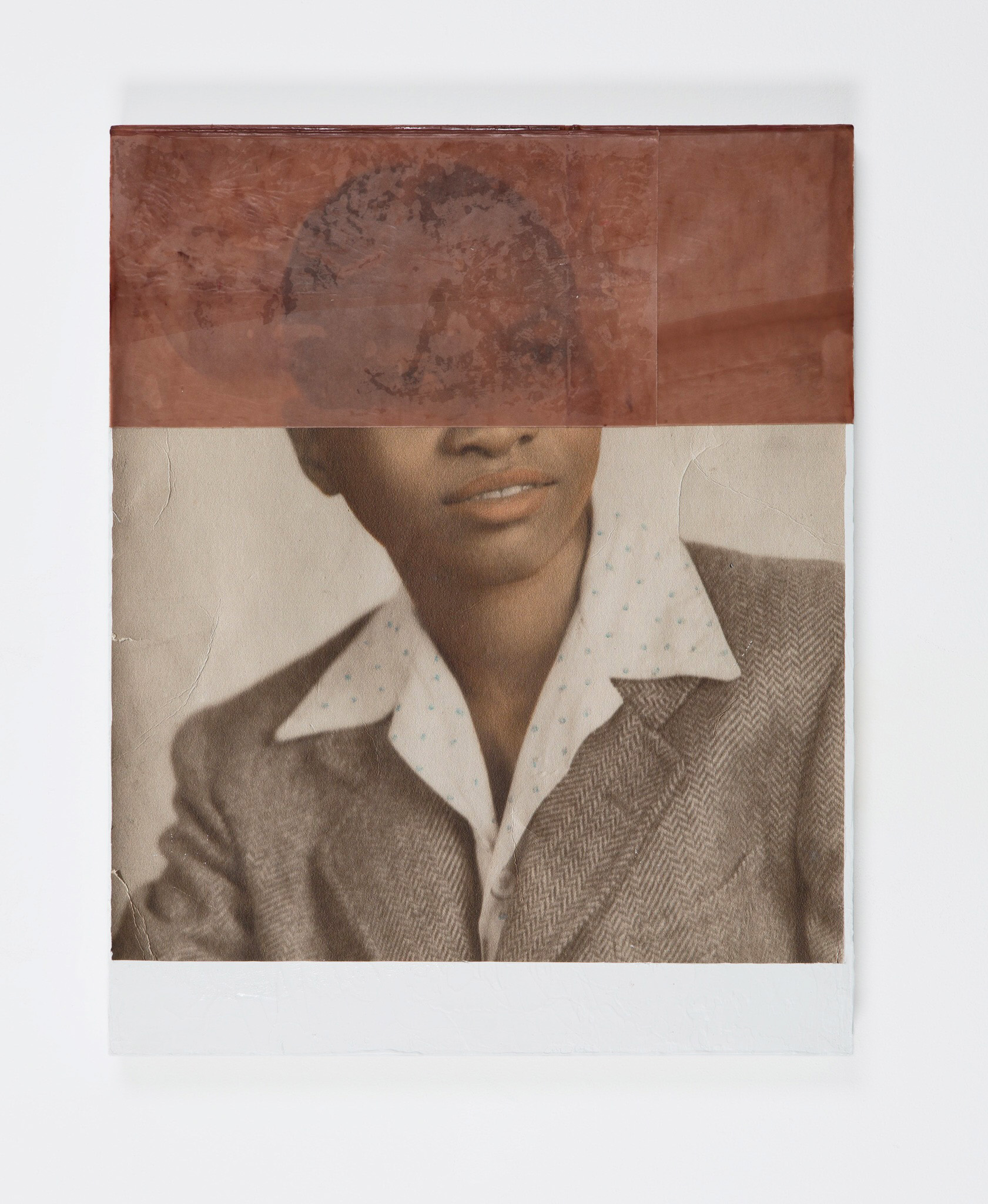

Gentle Woman, 16 in. x 20 in.,

Digital Inkjet Prints, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, Oil, on Panel, 2019

Past Tense, Future Present, Six 8 in. x 10 in. Panels, Digital Inkjet Print, Wax, Japanese Kozo Paper, Acrylic, Black Vinyl, on Panels, 2019

JL: You recently co-curated an exhibit at Baxter Street Camera Club in New York, Por Los Ojos De Mi Gente (Through the eyes of my tribe), inspired in part by the pioneering and often overlooked transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. Can you tell us more about the exhibit?

AF: I had the wonderful opportunity to co-curate Por Los Ojos De Mi Gente alongside my fellow Baxter St. resident Antonio Pulgarin. We wanted to put a lens to Black and brown queer representation through photography. Antonio and I, who both work closely with archives, were interested in queer artists who are creating their own archives and pushing forward new representations of queerness and queer identity through portraiture.

Severed Gently, 8 in. x 6 in., Digital Inkjet Print,

Wax on Panel, 2019

JL: What are you working on currently or what is next for you?

AF: AF: I’m currently preparing for my upcoming solo exhibition in May at Baxter St. CCNY which will include new work. I have a recent feature in Aperture Magazine’s Utopia Issue, which will be followed by a talk hosted by Aperture and JW Anderson on Feminist Futures on February 4th. I also have an upcoming feature in Light Work’s annual Contact Sheet. I will be in an upcoming group exhibition at the University of Minnesota in 2021. All of which I am very excited about. I’m working on some other projects that I can’t yet talk about but there will definitely be more soon.