An Interview with Andrea Grützner

February 12, 2026

My first encounter with Andrea Grützner was as a generous stranger. I was living in Berlin in 2022 and had some prints to scan and no access to facilities to do so. We connected through a mutual friend and I showed up at Andrea’s apartment where she passed off her brand new Epson V850 to me with no questions, deposits, or reference checks. I was stunned and grateful.

I later learned that Andrea is a well-known photographer whose work is frequently exhibited across Germany and internationally, including at Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Haus Gropius Dessau, Henie Onstad Kunstcenter Oslo, Goethe-Institut Paris, Camera Club New York City, and the Centre for Contemporary Photography Melbourne. Her celebrated project Erbgericht was selected to be a part of Foam Talent in 2016, and was published by Hartmann Books in 2024.

Andrea’s work considers how space, architecture, history and memory intersect within the flattened plane of a photograph. In her images, the familiar appears strange: the world turned upside down and alive with color. “Photography is like its own space—it reflects and mirrors the real world, people, or events,” Andrea writes, “but in a way that's always an optical, political, psychological, and artistic translation.”

Born in 1984 in Pirna, Germany, Andrea lives in Dresden and teaches regularly at German universities. She earned her MA in Photography and Media Design from Hochschule Bielefeld in 2014, focusing on conceptual and artistic photography, and previously studied Communication Design at HTWG Konstanz.

—Jessina Leonard

![]() From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 28, 2020

From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 28, 2020

From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 2, 2014

JL: Play seems to be an essential part of your photographic practice, both while photographing and in post-production. I am especially interested in what this looks like while photographing—using the camera as a magic wand, as you have written. What does your process of making pictures look like?

AG: Play is such an important strategy for survival. Now that I have a child, I am confronted with the immense power of creativity and fantasy—it actually makes me speechless! Play in general holds strong possibilities for experimentation, discovery, and community, and thus the potential for transformation.

More than a decade ago, when I started my work Erbgericht, my methods and aesthetic were strongly influenced by an intense occupation with the idea of heterotopia, originally developed by the philosopher Michel Foucault. I was digging around his early texts about modern French literature and how he developed the concept of the ‘other space’ from it. I translated his stylistic figures from literature into photography and combined it with my obsession for this 125-year old country inn in Eastern Germany called Erbgericht. It has been a frequent gathering spot for my family and also a heterotopia par excellence. This weird combination of reading Foulcault and photographing in this familiar space led me to experiment and play with lights and color gels.

All these ideas of lingering space, in-betweens, thresholds, mirrors and traps, symbols which are changing sides and in limbo are still working in my mind and feed into my artistic practice. I am drawn to images that are transforming reality (whatever that is!) into something else, while still keeping traces and hints of the ‘original’ place.

Very often, I start with collecting a lot of material, pictures, historical references, and texts in boxes and scrapbooks and try to find my own form of transformation depending on the topic. And this process can sometimes take years. Coming back to your initial word, play: while expermentation has always been a part of my work, I am now wondering if and how I can be more spontaneous in-situ in my artistic process.

JL: Your series, Erbgericht, documenting the interior of an inn in Polenz, Germany, a frequent family gathering spot, gained a lot of attention early in your career and established your voice as a photographer. What led you to working with the color flash in this work? And, in general, what draws you to working with such vibrant color?

AG: It’s been an exhausting trajectory. At the beginning, I took very traditional documentary pictures of the space, always when I was struck by the atmosphere and light in it, or during all kinds of different events taking part in it. But I somehow didn’t feel the images, especially the ones from its interior, although I was so entranced by the space itself. With these pictures, it lost its haunting and poetic aspects. Instead, I only saw the repetition of stereotypes in the contact sheets—a melancholic and nostalgic cultural space in the countryside. This was not me. (Although, I’ve started to see potential in my bold graphical markings that I made on the contact sheets in order to find new images.)

My initial thought of using the flash was ‘to kick out nostalgia through its brutality.’ And it struck me that the flash was, in a way, cutting through the space like a chainsaw. As I liked the intrusion of the red and yellow markings, I started experimenting with color gels in front of my flashes. Many older inhabitants of the village were sharing with me stories and memories of the country inn. They somehow colored its interior with all their projections and emotions. For me, a lot felt familiar but at the same time unfamiliar and unreachable: like shadows, which are a metaphor for memory and, also, the essence of photography itself.

From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 7, 2014

JL: You recently published a book of this work with Hartmann Books. Can you talk about the process of translating this work into the book form? How did you develop the sequence for the work?

AG: This was a challenging project for me, especially since the work doesn’t follow a typical narrative structure. Instead, it’s connected through more abstract ideas. I wanted to find a way to weave the main images of the interior with something else, something that could act like chapters in an anti-narrative story, adding contrast, hints, and traces along the way. It was important for me to let the ghost of the house sort of sneak back in through the back door, so to speak.

The idea of rotating all the images 90° came up early in my collaboration with my friend and graphic designer, Johanna Floeter. It was a simple design choice, but it opened up a lot of different ways of thinking: How do you navigate through the book and the space? What’s your orientation in the space and within the images? Are you looking at one image or several at once on each spread?

It also freed us from the usual approach of combining images on spreads or creating a classic image catalogue. It gives us the freedom to show the images as large as possible without needing an overly large book and it also gives the feeling of shifting space as you flip through the pages.

These were the main ideas we discussed in our first long working session, and we also talked about including a more socially poetic text in between the images. After that, I spent several months reworking and rearranging the sequence from time to time, always feeling like something was still off, until, after some time, it finally came together and felt right.

The book starts with double-exposure photograms, created by exposing a large bunch of keys (including keys to the "foreigner rooms") onto black-and-white negatives. Then, there’s an image of a cellar staircase where you can’t quite tell if you’re looking up or down. The book ends with a staircase leading to the attic, along with scanned color gels from my working process with flashlights. All the images in between are connected by their formal and vivid color elements rather than by a clear narrative.

The poem by artist Eric Meier, which he wrote in response to this work, provides some historical and social-emotional context. The idea with the foil around the book came later, as we wanted to add a playful element to it, which gives hints to my artistic process. The text provides elusive references to periods of transformation, the post-reunification era, and current societal issues.

Bunch of Keys 5, 2024

Erbgericht by Andrea Grützner, photograph by Clara-Lilian Berger

Erbgericht by Andrea Grützner, photograph by Clara-Lilian Berger

JL: Like you mentioned, a word you often use in relation to your work is Michel Foucault’s idea of heterotopia, how particular spaces—like cemeteries or prisons—bend, change and transform, resisting and expanding their boundaries and making other kinds of spaces possible. How does this idea relate to how you think about photography itself?

AG: Photography is like its own space—it reflects and mirrors the real world, people, or events, but in a way that's always an optical, political, psychological, and artistic translation. It’s got this strange sense of time. The image itself has its own rhythm while often giving a clue about how long it took to capture. Photography can stretch time, compress it, or even layer it with things like multi-exposures. And the same goes for places. It’s an illusionary medium, but somehow it’s really good at hiding the fact that it always creates its own kind of reality, fiction or legends. I’ve always been fascinated by how photography can create spaces that feel like they’re in-between, suspended moments or strange creatures in that limbo.

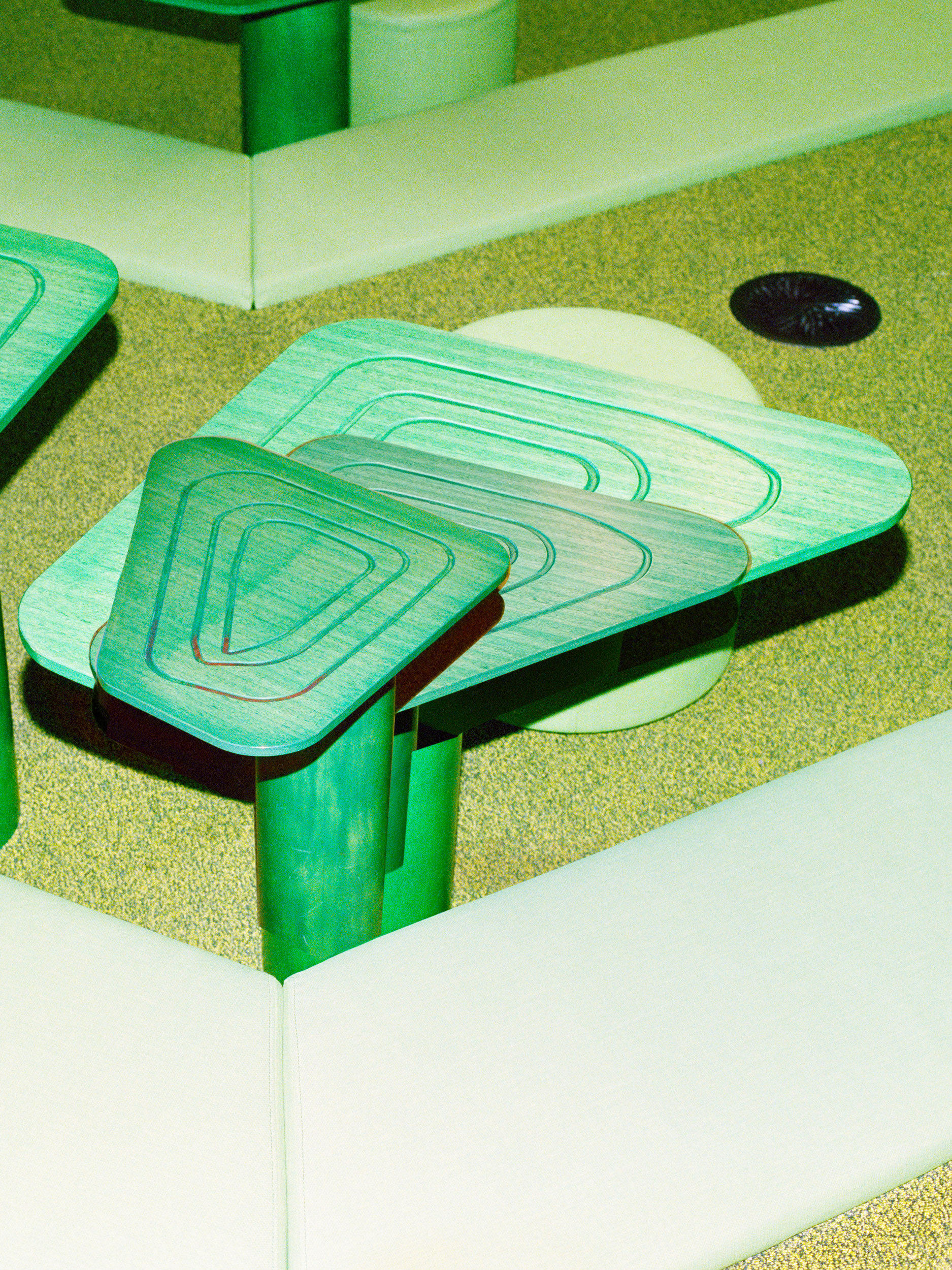

Installation of Arkadia, Paris Photo 2025, photography by Christopher Littlewood for Robert Morat Gallery

JL: In your work, Arkadia, which you recently exhibited at Paris Photo, you transform a grassland at Neukladow Estate Park into what you call "chromatic excess." These phototographs glimmer and leak color, at once natural and artificial. What is significant to you about this site in particular and what brought you to—quite literally—look down?

AG: In 2021, I was invited to take part in a summer academy at Neukladow Estate Park on the Havel near Berlin. The program was conceived as a plein-air setting that encouraged working on site and engaging in conversation with visitors and other artists. The park itself is historically charged. In the 1910s, the art historian Johannes Gutmann lived there with his partner, redesigning the estate as a refuge for prominent figures of Berlin’s cultural scene. A close friend was the Impressionist painter Max Slevogt, who described the park in almost paradisiacal terms and painted it in shimmering colors.

Today, the site still appears idyllic, but on closer inspection it reveals many traces of human intervention and ecological stress. The summer I was there was unusually intense, with heat and drought already shaping the landscape. I was drawn to a long meadow at the edge of the park, where a tributary of the Havel once flowed. Looking down became a way of responding to the absence of water and to the layered history embedded in the ground.

I initially worked with glass reflections to suggest water, and later with dichroic film that refracts light into shifting colors while filtering specific wavelengths, a material material often used to block UV radiation. The resulting almost psychedelic excess felt like a resonance chamber: between the art-historical legacy of the site, the fragile, almost deceptive idyll of the landscape, and a moment of pleasurable loss of control. Looking down became a way of attuning myself to these layered temporalities—where paradise, artifice, and ecological unease coexist.

The Zenith, Ever Further, 2023

From the series Hive, The Learning Centre, 2019

From the series Hive, Connect, 2019

From the series Hive, The Lawn, 2019

JL: In your series, Hive, you digitally manipulate images of university architecture, considering these spaces as representative of the alienation of modern society and the erasure of a distinction between leisure and work. These alluring yet strangely empty pictures make me think of Lauren Berlant’s idea of cruel optimism, when something we desire is actually an obstacle to our flourishing. How do you understand the power of architecture in shaping our desire?

AG: Thank you for pointing out Laura Berlant, I haven't been familiar with her work but it indeed seems to fit pretty well.

In Hive, I explore a university architecture that looks playful, colorful, and full of energy. The spaces I photographed at RMIT in Melbourne are designed to be creative and stimulating. They remind me of retro video games, theme parks, or science-fiction films, which are all places that promise progress, imagination, and joy. These learning and leisure environments seem to support new ways of thinking, working and being together.

But at the same time, they are also highly designed to shape behavior and ideals. The architecture encourages things like constant flexibility, productivity, creativity on demand, and visibility. These are all values that are central in today’s neoliberal society. In that sense, these spaces do not only support learning, networking and living, they also control it.

Lauren Berlant’s idea of cruel optimism helps me reflect on this contradiction. She describes how we become attached to things that we believe will help us thrive but that may actually prevent us from doing so. These "objects of desire" feel good, but they come with hidden costs. In the case of Hive, the architecture looks open and full of opportunities, but also carries subtle pressures and demands. In my work, I emphasize this tension through image manipulation and the use layering, collage, and forms of distortion. I exaggerate the visual qualities of the space, to show how the optimistic promise becomes unstable and uncanny. The rooms seem fun and creative, but also confusing or overwhelming. They attract us and trap us at the same time.

We hold on to dreams or ideals that probably no longer serve us because we are deeply attached to them. Hive explores this emotional and spatial ambivalence through visual language. Douglas Spencer also has great thoughts in Architecture of Neoliberalism regarding how architecture has become an instrument of control and compliance. And I found a great small book called JUNKSPACE with RUNNING ROOM with essays by Rem Koolhaas and Hall Foster, who add other thoughts on these topics.

JL: You grew up in the GDR before moving to the West after the fall of the Berlin wall. How, if at all, does your childhood experience influence your approach to your work, especially Erbgericht?

AG: This question brings up many emotions and thoughts, especially concerning how my family, community and society shaped my worldview during childhood. My upbringing was very loving and also often strict, with many rules about how to behave as a child and a young girl back in the days, also related to GDR society. Still, I was very young when the wall opened and soon after my parents, my sister, and I moved to western Germany. I’ve always been a daydreamer, someone who loved to draw and build things, but I was often told, especially by my grandmother, how to do it properly, which felt somewhat limiting. So, presenting this traditional institution Erbgericht in a contemporary and very personal way through the joy of colorful abstraction could also be seen as a form of artistic rebellion and deconstruction of existing narratives. Another unconscious influence might be my explorations through this huge building during family gatherings back then, when I would escape for a few moments to explore.

Looking back now, the values, propaganda, and the difficult, ambivalent transition period of the “Wende” still shape societal tendencies more than ever. The Wirtshaus Erbgericht, with its walls full of memories, embodies both the traumas and still the beautiful moments of those times. Symbolically speaking, it holds the echoes of those transformations. And I was searching for a way to create something like a utopia, something completely different but still connected to the original place. In doing so, I also tried to translate a lingering feeling of vertigo, that quiet nausea born of history, displacement and change, into images.

JL: Light and shadow become sculptural in your photographs, often creating three-dimensional spaces that are as familiar as they are uncanny. What is your relationship to light?

AG: When I was younger, I used to say a little prayer to the setting sun, asking it to come back the next day. It's strange, because I wasn’t raised religiously. It was my own little spiritual ritual every day. I felt like a moth drawn to the light, always fascinated by beams of light hitting things and dancing through elements. This sense of wonder has stayed with me, often stopping me in my tracks, sometimes maybe too often. The strange and beautiful thing is that it seems so hard to actually "catch" these moments in a photograph without ending up with pure melancholy or kitsch. I have hundreds of images like this. And this is also why I was desperately searching for a different expression in Erbgericht itself. It all started with the beautiful evening sunlight hitting a bunch of dried flowers in an abandoned wardrobe… an intense, poetic feeling in that moment, yet it felt superficial and full of clichés when I saw it on the contact sheets. Still, I admire lots of photographic images (and photographers), who handle light in a beautiful and touching way. It’s a gift, if you’re able to do it.

From the work Erbgericht, Untitled 5, 2014

JL: Last, I am curious what is some of the best advice you have received as an artist?

AG: Try to trust and believe in yourself and your topics. I know that sounds a bit cheesy, but it's really hard to do. At least for me, other voices often take over, and after a while, you start to think those voices are your own. So this isn’t just artistic advice, it’s more of a general one: if you feel something, an emotional state or a way of thinking that might seem strange to others but makes sense to you, you’re allowed to follow it.

My professor, Katharina Bosse, gave me a lot of good advice. One thing that stayed with me — and that I really need to return to — is that as a photographer you need physical strength and a lot of energy. So it's important to do something active, like sports, and all sorts of things that give you energy. But again, that's useful for everyone, not just artists.

She also encouraged us to think more about our networks, which is something I could definitely improve on. Lately, I’ve been coming back again and again to Rick Rubin and his thoughts on creativity. They can be helpful and soothing, especially in moments of doubt.

From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 28, 2020

From the series Erbgericht, Untitled 28, 2020