An Interview with Dionne Lee

July 15, 2020

I first met Dionne Lee earlier this year when she generously made a virtual visit to a class I was teaching on experimental photography. As her work often draws on found images from wilderness survival guides, much of our conversation that day situated around questions of survival—not only who survives, but who is positioned to survive? Now, just a few months later, amidst a global pandemic and increased attention towards the persistence of racial violence in the US, these questions seem even more urgent.

Using photography, collage and video, Lee investigates ideas of power and racial histories in relation to the American landscape. Whether it be working intuitively in the darkroom or performing her own gestures of survival in the landscape, the body takes on a central role in her work as she examines humanity’s interdependence with nature.

Lee's work has been featured in numerous exhibitions including The New Orleans Museum of Art, the San Francisco Arts Commission, Light Work, and Aperture Foundation. Lee was a finalist for the 2019 SFMoMA SECA Award and the 2019 San Francisco Artadia Award. She was Art Forum’s Critic’s Pick in 2019 and currently teaches photography at Stanford University.

—Jessina Leonard

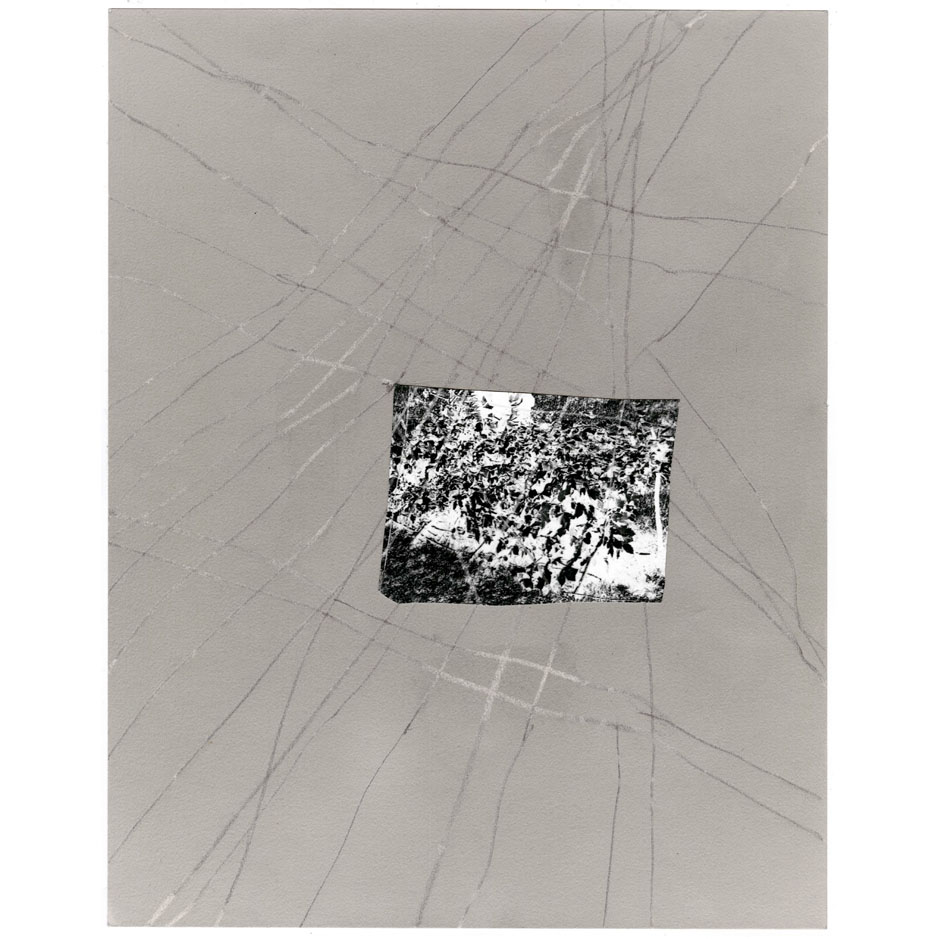

Building a Bed, Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

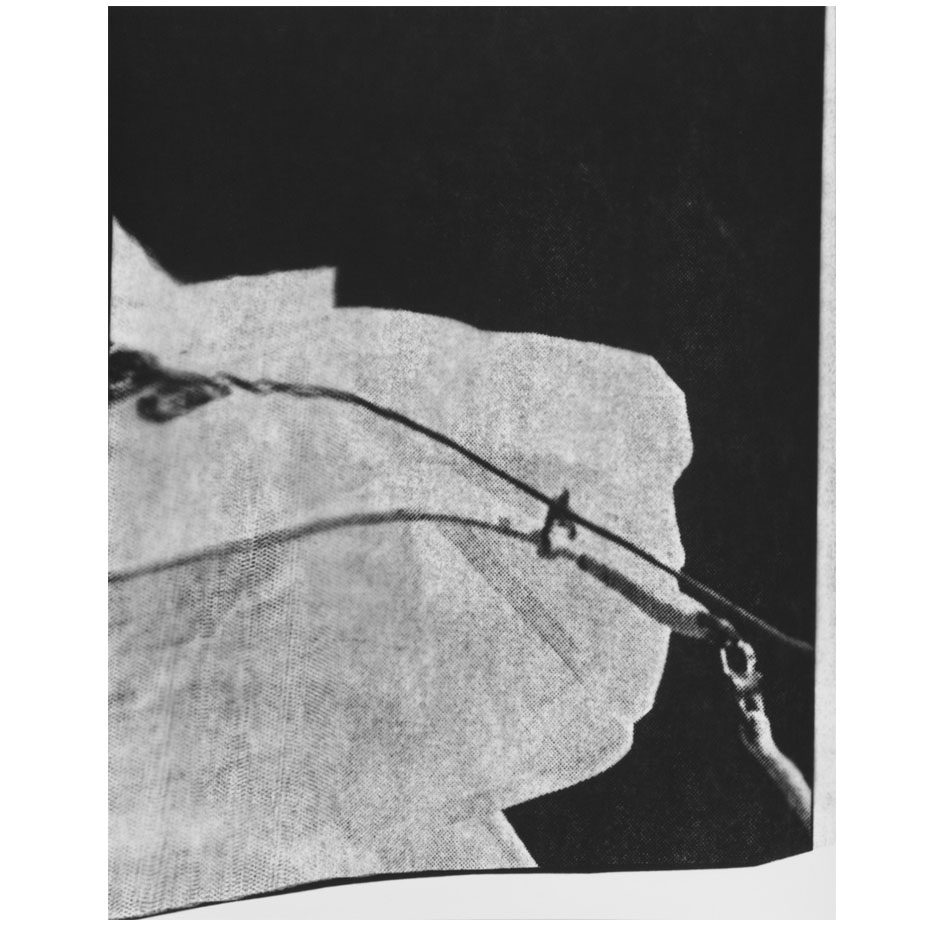

Fleet, Gelatin Silver Print, 2019

JL: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me today, Dionne. Your work speaks to the inherent political nature of the American landscape and the myth of the “natural,” and yet you are from New York City and currently live in Oakland. So, I wonder where your interest in the natural world began?

DL: My interest in the outdoors began quite early, actually. I am a New Yorker (born and raised!), but I was fortunate to grow up in Harlem, across the street from Central Park. I think growing up where I did fostered a different kind of relationship to the city and landscape in general . . . nature was easily accessible to me, even if it was man-made. It wasn’t until adulthood that I learned parts of Central Park were once Seneca Village, a community of free African-American property owners. Far before that, of course, the Lenape people were stewards of what we know today as New York City and the greater Tri-State area. My parents also cared for many houseplants and I was fortunate enough to attend sleep-away camp a couple of times, which was my first true experience in the wilderness. Much of my childhood and early adulthood I was actually afraid of these spaces—they got dark, they weren’t filled with people . . . and it’s sort of funny now, but I think the movie, The Blair Witch Project, really enforced an early fear of the woods. I was 11 years old when that film came out and I believe I saw it in theaters.

Anyway, as an adult I became interested in herbalism and began learning the names and properties of many plants (mostly classified as weeds) in the city. Upon learning that these “weeds” held many healing properties for both people and the land, my perspective shifted and I began to understand on a deeper level the interdependence between humans and the land. I’ve lived in California, on unceded Ohlone land, for almost five years now and am still learning more about the land of the West.

JL: What artists, writers or particular landscapes inform your practice and research?

DL: In grad school, when I came into a deeper understanding of not just my interest but also my relationship to the natural world, I came across the work of Camille Dungy. Dungy edited an anthology of poetry: Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. I’ve always been a student of poetry and coming across this book brought on a huge shift for me. It put words to so many of my feelings and also gave me a sense of company, as did the book Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. I’d say both books are personal touchstones as well as resources I keep in my studio.

Recently my work has revolved around the idea of survival. Since moving to California I’ve been collecting wilderness survival guides. I think they are often seen as an antiquated resource, something not needed in the 21st century when we have every technological tool imaginable that we think can save us from most situations, but personally these books speak to my own anxieties of an apocalyptic future (or present) and to evidence of the persistent truth that land and people are forever in a state of interdependence.

Netting, Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

JL: I keep returning to your piece, A Test for 40 Acres, where you photograph a field covered in mylar blankets in reference to the government’s promise of 40 acres and a mule to African Americans after the abolition of slavery, a promise which was never fulfilled. Could you walk us through your process of making this particular piece?

DL: There is actually a funny story here . . . when I set out to make this piece I had no idea how big 40 acres actually was (that’s the city kid in me). I was interested in the emergency blanket as a material—a tool for survival and signaling in a dire circumstance, an insulator, and a reflector of light. My original plan was to make a 40 acre emergency blanket and consider how it could function on open land: what’s the crisis that has taken place? What is, if anything, being reflected back to us? I sat in my studio for a few weeks just piecing together these blankets and sort of assumed I was getting close until I did the actual math. Something about my inability to comprehend the true size of 40 acres felt deeply tied to repercussions of that loss of property. The work then became not just about the failure of the government, but my own failure in not being able to complete the project as intended. The piece then became a proposition, or a test as the title implies, potentially leaving room for another attempt.

A Test for 40 Acres, Archival Inkjet Print, 2016

Fire Bed, Gelatin Silver Print, 2019

JL: Your work is rooted in the ways in which the American landscape has been a source of both consolation and violence for African Americans throughout history. But, I cannot help but think about how any ideation of the American landscape is inseparable from how photographers like Edward Weston and Ansel Adams shaped a cultural understanding of the landscape as ideologically neutral. Your work pushes back on this idea. How do you understand your work in relation to this photographic history? Is the experimental nature of your work important to this?

DL: Yes, absolutely. I would even push this a bit further: unintended or not, photographers like Weston helped create this cultural understanding of the land as neutral, but in creating this “neutrality”—which to me is a false claim to begin with—their work was actually used as a tool for land domination and white supremacy. Years ago I came across an old lynching card that was circulated in Texas . . . on the card there was an image of a person lynched from a Dogwood tree and a lyric poem on the back literally aligning the tree itself with white supremacy. Nature is often presented and discussed as a neutral space, but we don’t talk about how nature can also be a tool. And when it becomes a tool its “neutrality” is lost.

A portion of my work is made from found images, much of which depicts nature as idyllic. When I cut up, tear, or alter these images I see it as a challenge to authorship and the false narratives perpetrated through early landscape photography.

Fleet, Gelatin Silver Print, 2019

JL: Whether it is in your photographic work, such as Floaters, where you print overlaid negatives of synchronized swimmers in reference to the compacted bodies of Africans forced onto ships during the transatlantic slave trade, or, in more sculptural work like Running, rigging, wading, a handmade rope hung directly in the gallery space, I am always very aware of the physical presence of a body, whether or not it is represented. Through references to escape routes, shelters, burials and survival, or even in the performative gesture of your own body in A Test for 40 Acres, there is a real sense in your work that something is at stake, a presence lingering in the shadows or at the end of the rope. I’d be curious to hear your own take on how you understand the presence of the body in your work.

DL: Yes, performing, processing, and researching through the body is really important to me. Much of my recent work explores how the body can be its own tool for survival. The pieces you mention all hold space for thinking about the body and its relationship to autonomy. Other works it shows up in are the pieces North and True North. In both images I am acting out a technique for measuring the distance between the Big Dipper and the North Star. Locating the North Star was a critical skill for Black people fleeing the South during and after enslavement. This gesture is so important to me as I think about how it lived in the bodies of my ancestors, how its importance or necessity has shifted, and how it is a gesture anyone with two hands can make. It is a skill that can be learned and not taken away; it will never fail as long as the North Star stays in place. Our body is ultimately our compass.

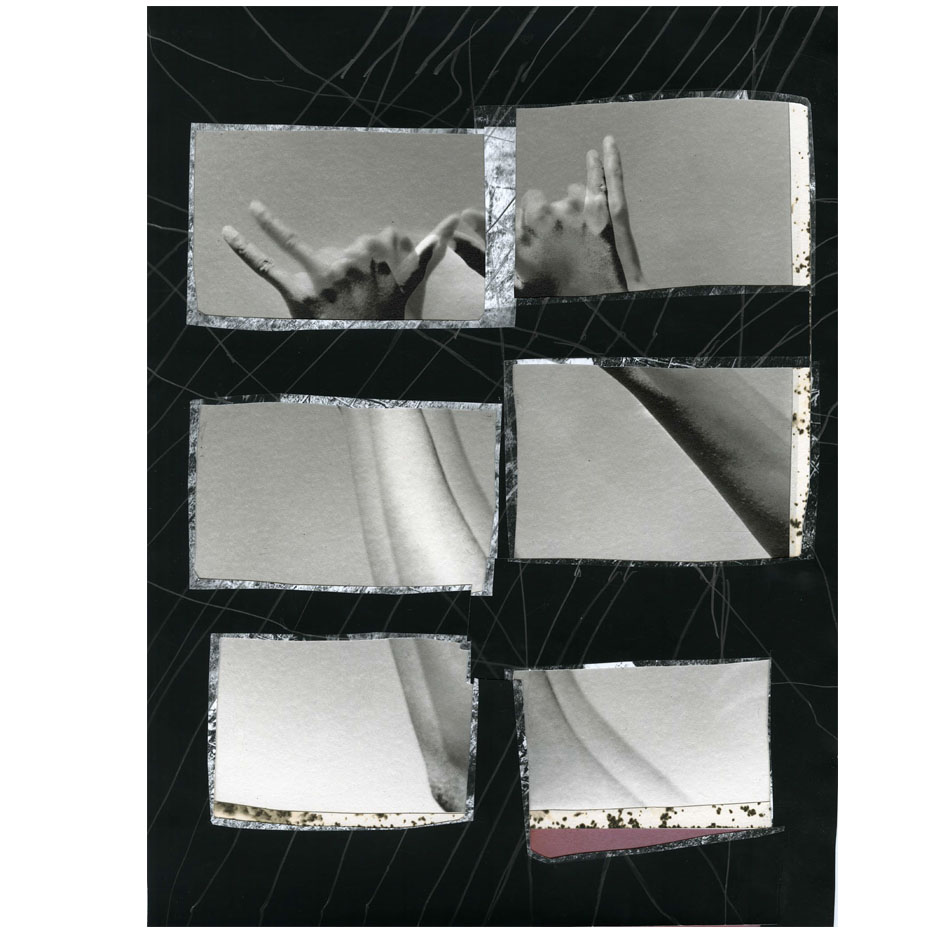

Loose Structure, Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

True North, Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

JL: When you spoke to my students earlier this winter, you talked about how skills for survival and, more specifically, wilderness survival guides serve as an inspiration, theme and often even material for your work. Although it is now only a few months later, I keep thinking about how those survival skills are all the more urgent now, amidst a global pandemic and increased attention towards the persistence of racial violence in the US. What have these past few months looked like for you? What have been your skills for survival and how has this time influenced your artistic work? (Perhaps too early to ask!)

DL: Oof. Yes. Self-sufficiency and survival feels more urgent and of the public consciousness of the moment. I often cite Afrovivalist who states her own awakening around safety and survival came after Hurricane Katrina and the sureness of knowing that black people and other marginalized communities cannot rely on the government to protect us. Amidst the current calls to reimagine public safety I think there is a real reckoning happening with how we define and envision survival—which to me is the bare minimum. The goal is to thrive. In regards to how current events are impacting my work . . . I don’t know yet. It’s been a lot to process. Responding in real-time doesn’t come naturally to me so I think things will come to the surface in their own time.

Warnings (2), Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

Warnings (1), Gelatin Silver Print, Collage with Graphite, 2019

JL: What are a few objects currently in your studio that are important to you?

DL: Oh I’ve got lots of notes from friends hanging around my studio that keep me company. One is a note that says, “IT’S A TRAP!” A mentor of mine, Aspen Mays, said this to me in graduate school when I was stuck in self-doubt and insecurities that prevented me from fully investing in my work at the time. To all the self-deprecating artists (all of us?)—it’s a trap!!!