An Interview with S. Billie Mandle

January 21, 2021

S. Billie Mandle’s practice is defined by what Simone Weil called “the rarest and purest form of generosity”—attention. Whether she is photographing the wall of Emily Dickinson’s bedroom or the dark interiors of confessionals, Mandle uses a large-format camera and long exposures to make a photograph that is unfamiliar to our scrolling gaze, a photograph that is not immediately rewarding and does not explain, comment, or gesture—a photograph that simply is.

I first encountered Mandle’s photographs of Emily Dickinson’s bedroom wall in a small room at the Danforth Art Museum. Three large-scale photographs hung only a few inches apart on the back wall, as if they were the three parts of an altarpiece. In that moment, I was struck by a feeling of unease looking at these images—there was nothing to look at. Like an ancient image used to aid in devotion, the photographs did not let me in, but rather, invited me to go inside myself. Unlike the algorithmic flow of images designed to consume our attention, Mandle’s photographs require participation and humility.

Mandle’s work engages with the politics, histories and paradoxes of architecture and place. She has exhibited her work at the Addison Gallery of American Art (Andover), Garden (Los Angeles) and Syo Gallery (Seoul, Korea), among other places. Her projects have been supported by grants from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the Taconic Trust and her work has been featured in publications such as Aperture and Cabinet. She is an Associate Professor of Photography at Mass Art.

—Jessina Leonard

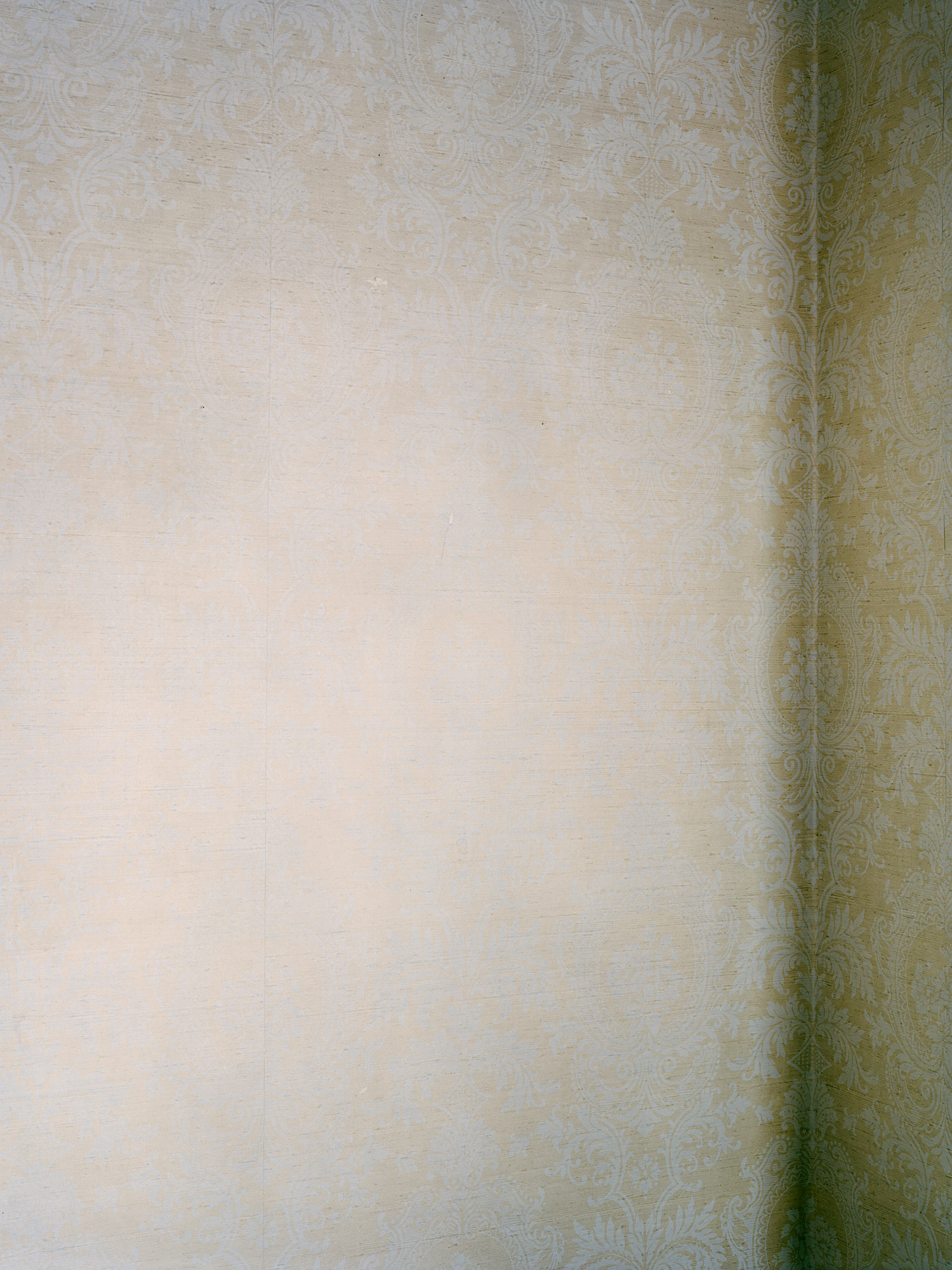

Untitled 15, 30 in. x 40 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Circumference, 2013 – 2014

JL: Throughout all of your work, your practice relies heavily on visual emptiness. Your photographs require the viewer’s focused attention—these are not images that are easily mastered or immediately understood. Is this always how you have made photographs? And, why is this mode of making photographs important to you?

BM: The art that I like is rather empty and quiet but rewards close attention. I draw inspiration from artists such as Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Zoe Leonard, Leslie Hewitt, Agnes Martin, Felix Gonzales-Torres. I think of emptiness as a kind of visual quiet. The author Kevin Quashie writes that: “quiet helps us to understand the activism involved in being aware, in paying attention, in considering.” I hope that the quiet in my work might lead to such attentive looking.

I photograph with the camera close to my subjects, and my images are often dark and flat—as you said there isn’t a lot to see in my pictures. Instead of inviting the viewer to visually move through an image, my photographs ask the viewer to stop and wait. I am interested in the opacity of images—the way they can prevent us from seeing.

The way I make photographs has always been slow and deliberate. Part of me wants to believe that if I just looked long enough at something I would understand it better—that some of its mystery would be disclosed. Of course that never happens—but as a photographer I put a lot of stock in just looking. Perhaps some of my searching will seep into the final photographs and the viewer will understand something that I did not.

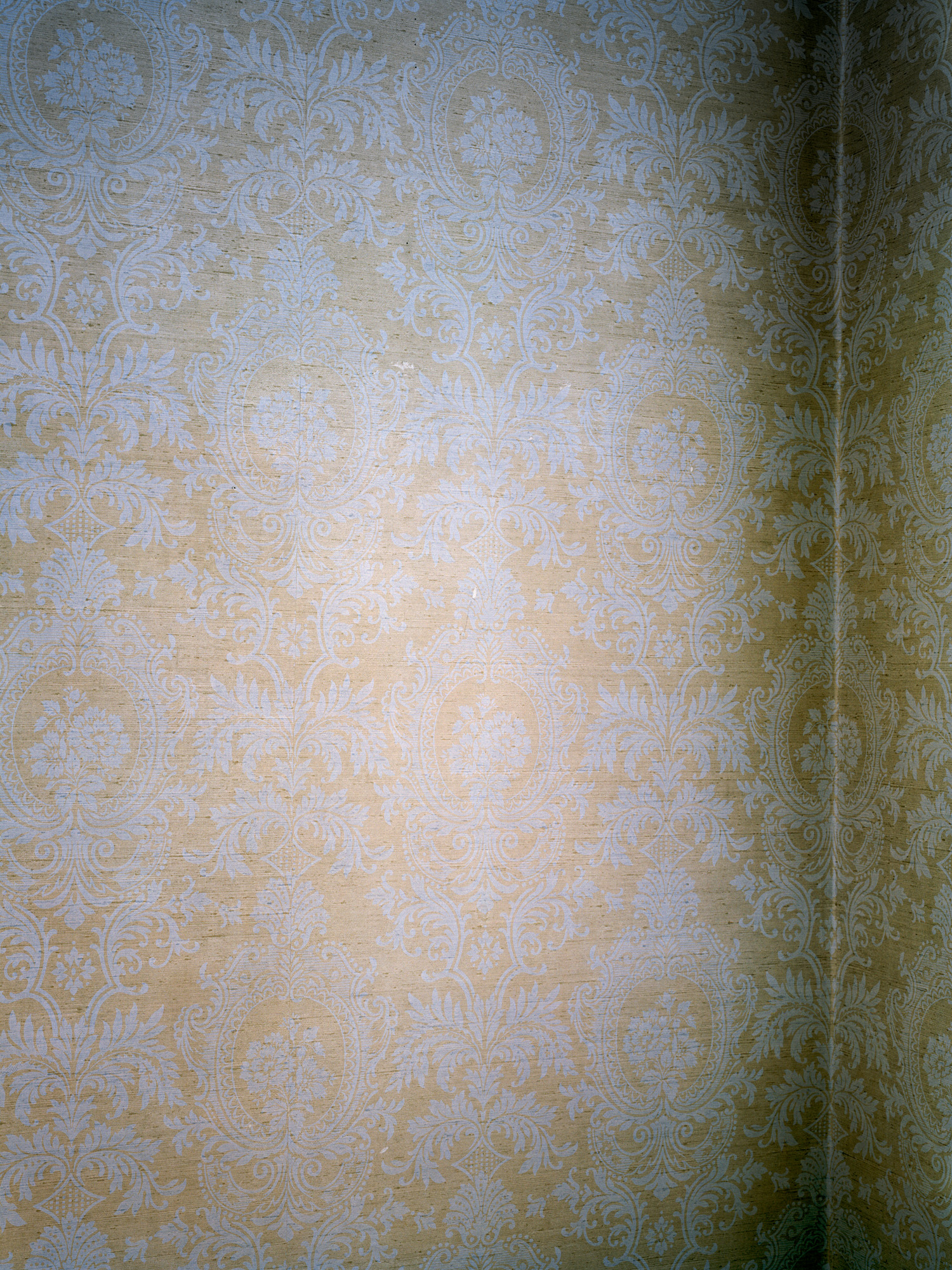

JL: In Circumference, you repeatedly photograph the same wall of Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, the very wall where she would have faced as she sat at her writing desk. When displayed together, the photographs invite the viewer’s attention to the subtle shifts of light in the room, showing the passage of time and linking the past to the present. Whether for this project or others, how do you interact with a space while making a photograph?

BM: I try to be present in the spaces where I photograph. As a child I lived a lot in my head and one of the reasons I like photographing is that the process requires me to be focused and present. My exposures are quite long and that gives me time to just be in a space, to think and observe. Sometimes, I use that time to write, sometimes I just sit and worry that the picture won’t be good. I really value those quiet moments though because I don’t feel like I have to do anything productive—the camera is busy for me. I should note that not all of the places where I photograph are serene. I photographed in a busy hospital and a home for refugees. Even the churches were typically full of people. But I still appreciate the long exposures. They give me permission to step outside of time and wait while everyone else keeps moving.

Holy Cross, 32 in. x 40 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series, Reconciliation, 2007 – 2017

Untitled 38, 30 in. x 40 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Circumference, 2013 – 2014

JL: In Reconciliation, a body of work recently published by Kehrer Verlag, you photographed Catholic confessionals throughout the United States for over ten years, a project that you describe elsewhere as perhaps your most personal body of work. What was the impetus for this project? What were you looking for?

BM: I began Reconciliation for many different reasons. Some were personal—I wanted to look more closely at Catholicism—the ways that it shaped my family and my sense of self. I was also thinking about forgiveness—the rituals we have for forgiveness and how we forgive one another and ourselves. Confessionals have long fascinated me—visually and conceptually. Confessionals and photographs have interesting parallels—both are dark, silent rectangles that hold traces of people’s lives.

This body of work became a way to explore intersecting ideas. A way to make dark photographs of dark places—and to grapple with dark experiences. I had no idea the project would last for so long.

JL: In a recent interview, you said that “...so much of photography is about power and control; I am interested in forms of seeing that are about humility and unknowing.” Why do you believe this mode of seeing—of unknowing—is important or urgent today?

BM: Teaching online this past semester made me feel like I was part of my computer. If a student had an esoteric question in class, or if I forgot the name of an artist, I could just look it up—everything was magically and immediately accessible. At the same time, the internet provides a false sense of knowledge and certainty. It is easy to forget how much we don’t know, or how much what we think we know is incomplete or wrong. American culture fosters glib confidence; I think we crave certainty at the expense of complexity. The crises we face today—white supremacy, the climate, neoliberalism—how can we approach any of these without humility and unknowing?

Saint Rocco, 32 in. x 40 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series, Reconciliation, 2007 – 2017

Untitled 70, 30 in. x 40 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Circumference, 2013 – 2014

JL: When I think of the term unknowing and your work writ large, I am reminded of writers like Meister Eckhart, Simone Weil and Dorothy Day, some of whom you have also referenced. What drew you to these writers in particular and what is the role of research in your work more broadly? And, what have you been reading recently?

BM: Some of those writers I began to read more closely while working on Reconciliation—and I continue to return to Simone Weil and Meister Eckhart. Since the pandemic I’ve been reading books on Buddhism. Right now I’m reading Oval by Elvia Wilk, The Prison and the American Imagination by Caleb Smith and several books about the California missions (the latter for a project I am working on). Research is important to my practice; I try to understand the layers of histories and narratives that define my subjects. Research helps reveal where and what I am photographing—helps me decipher what is visible but not obvious. Research also leads to what is still unknown about subjects—the narratives that have been silenced, hidden or overlooked. Not all of this can make it into my photographs but I hope it floats around them.

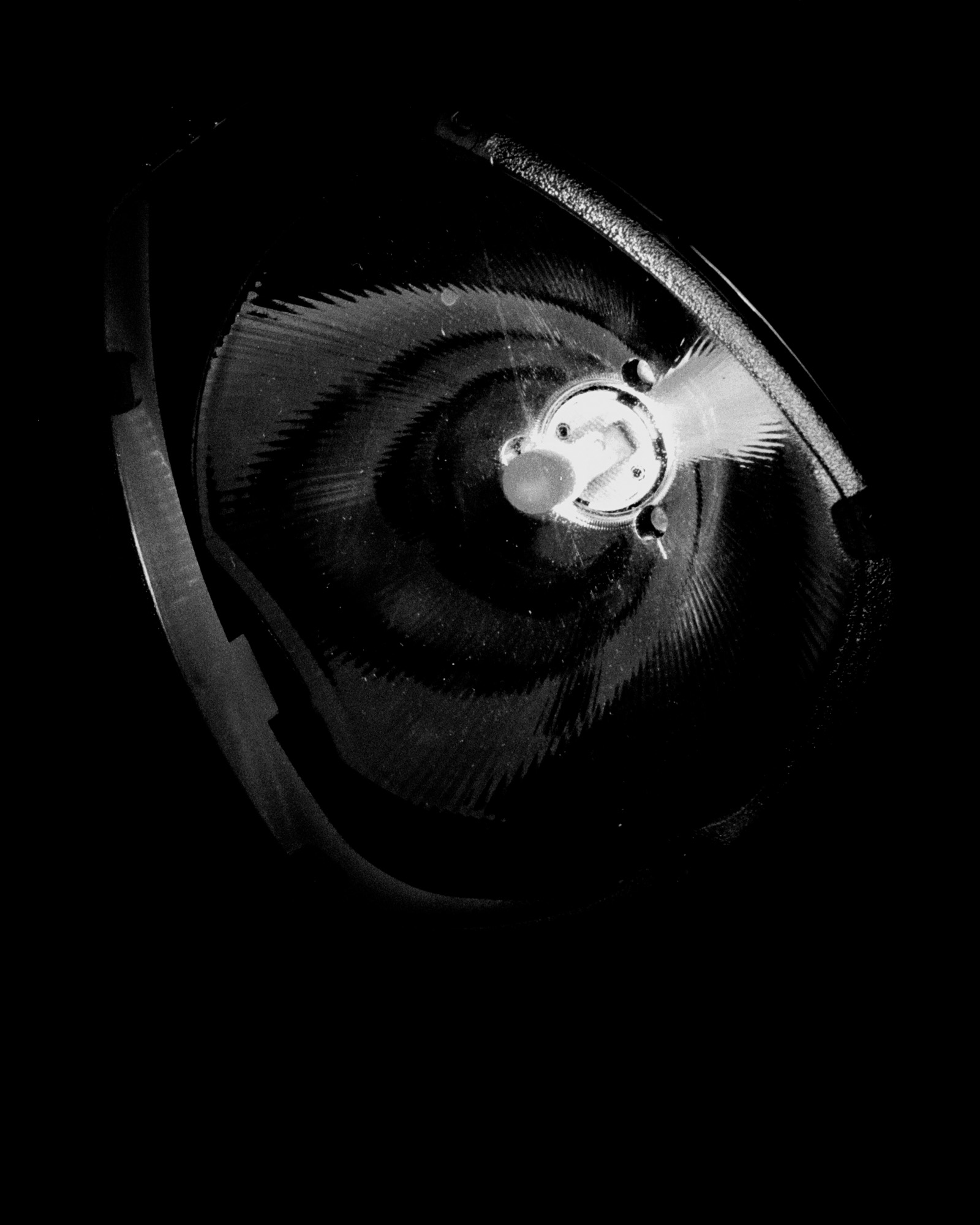

Untitled 11, 20 in. x 24 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Stellar Skytron, 2016-2019

Untitled 1, 20 in. x 24 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Stellar Skytron, 2016-2019

Untitled 6, 20 in. x 24 in., Archival Pigment Print, from the series Stellar Skytron, 2016-2019

JL: You recently published another book, Stellar Skytron, in response to your experience of birth and new motherhood. However, the book does not show pictures of either—instead, you offer the viewer what you yourself saw as you gave birth: the surgical lights above you. What struck you about these lights, either during the very moment of giving birth, or later as you reflected on the experience?

BM: Throughout my pregnancy I had wanted to photograph the ceiling of the room where I would give birth. I wanted to document a shared visual experience—what the baby and I saw together. I brought my 4x5 to the hospital with me. But then I had a c-section and was in no shape to photograph anything. Lying in the operating room, the lights were such a focal point of the entire experience I realized it made more sense to photograph them. I went back a few weeks later. I ended up making dark, abstracted photographs of lights. The first light my son saw. Or since newborns don’t see well, the first light my son felt.