An Interview with Sara Perovic

July 29, 2020

On a recent trip to a local bookstore, I discovered Croatian artist Sara Perovic’s book, My Father’s Legs, published by J&L Books in 2020. In this body of work, Perovic photographs her partner’s legs over and over again as he takes on different poses in reference to her own father’s obsession with tennis.

“Obsession is the main trigger of my work,” writes Perovic. Whether it is palm trees, her partner’s legs, or motherhood, Perovic uses her camera to riff on a theme with an unflinching sense of immediacy. When flipping through My Father’s Legs, I couldn’t put a finger on why I kept wanting to look and look again. Was it because of how unusual it is to see a male body objectified in this way—a catalog of legs, as Perovic writes—or was it something else, something about these fragments of vision that reverberate through space and leave the viewer searching for a sense of balance?

Sara Perovic’s photography is driven by her interests in the perception of space, abstraction, repetition and feeling of self. Her work focuses on textures (Palmeral, 2017), depicts the invisible (Bura, 2015), and shows nature’s fragility with ethereal photographs (I Was There, 2015). Her latest project (My Father’s Legs, 2020) is a mix of concept and emotion, stretching the boundaries between conceptual art and art-as-therapy. Among several solo and group shows, she founded and curated the fanzine aTree, promoting young photographers (available at MoMA Library), and currently works as a photographer and architect in Berlin.

—Jessina Leonard

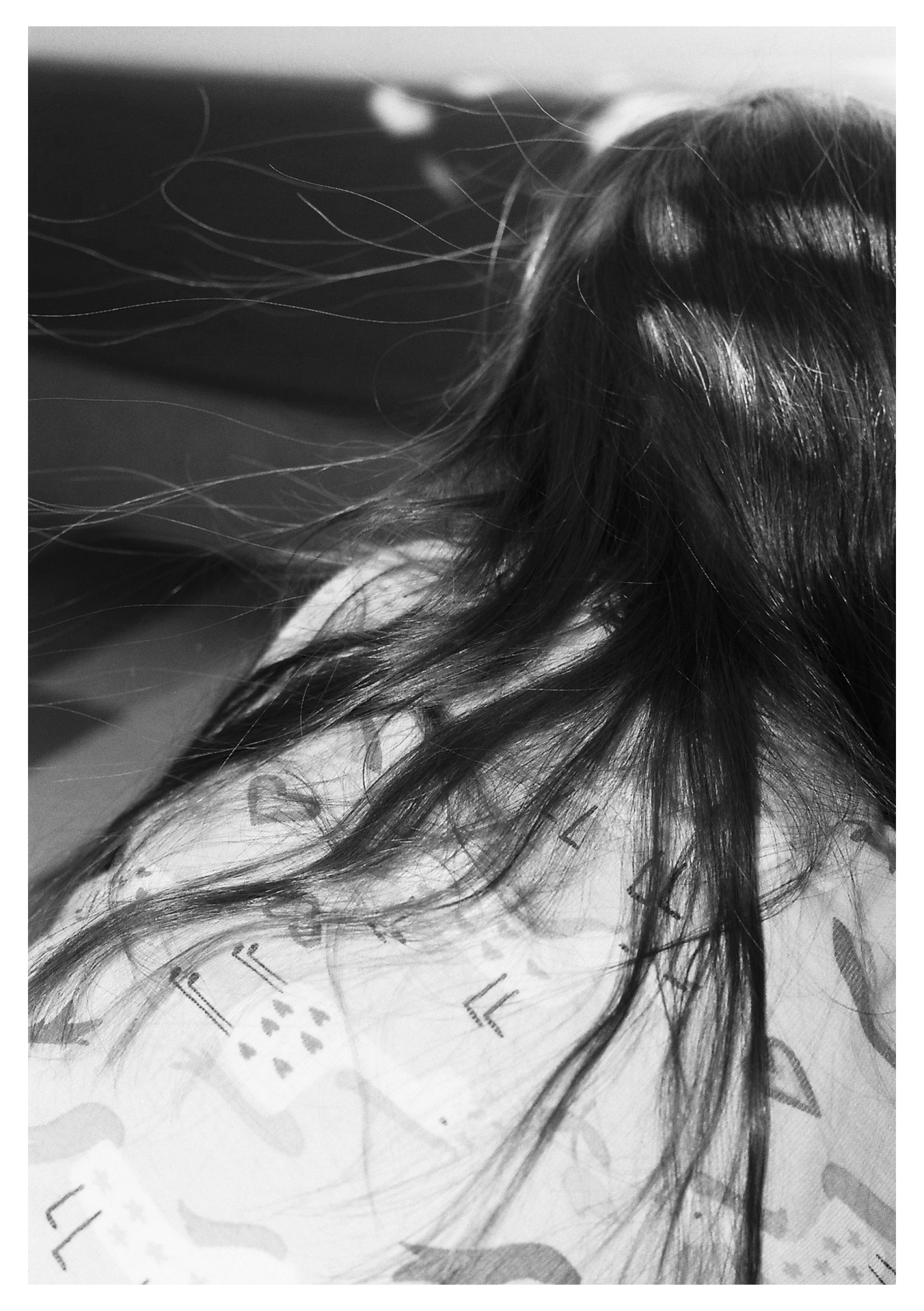

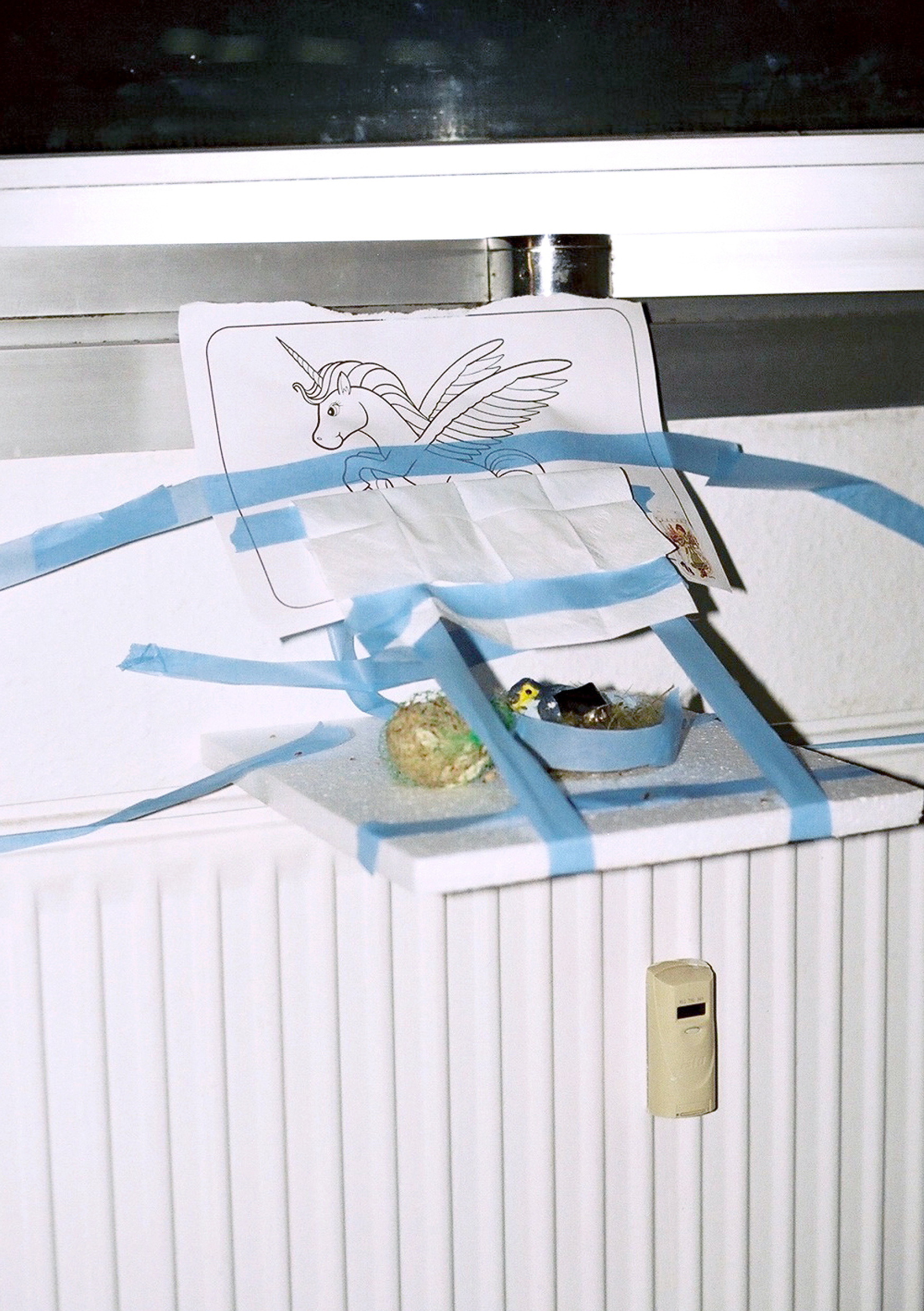

from the series WOMB, 2020

JL: Your recent project, My Father’s Legs, begins with the text, “My mother told me, ‘I fell in love with your father because of his beautiful legs.’” But the majority of the photographs in the book, apart from some archival images, are photographs of your partner’s legs. Could you talk about how this project began and how you understand your relationship to both your father and your partner? What was the impetus for this visual comparison?

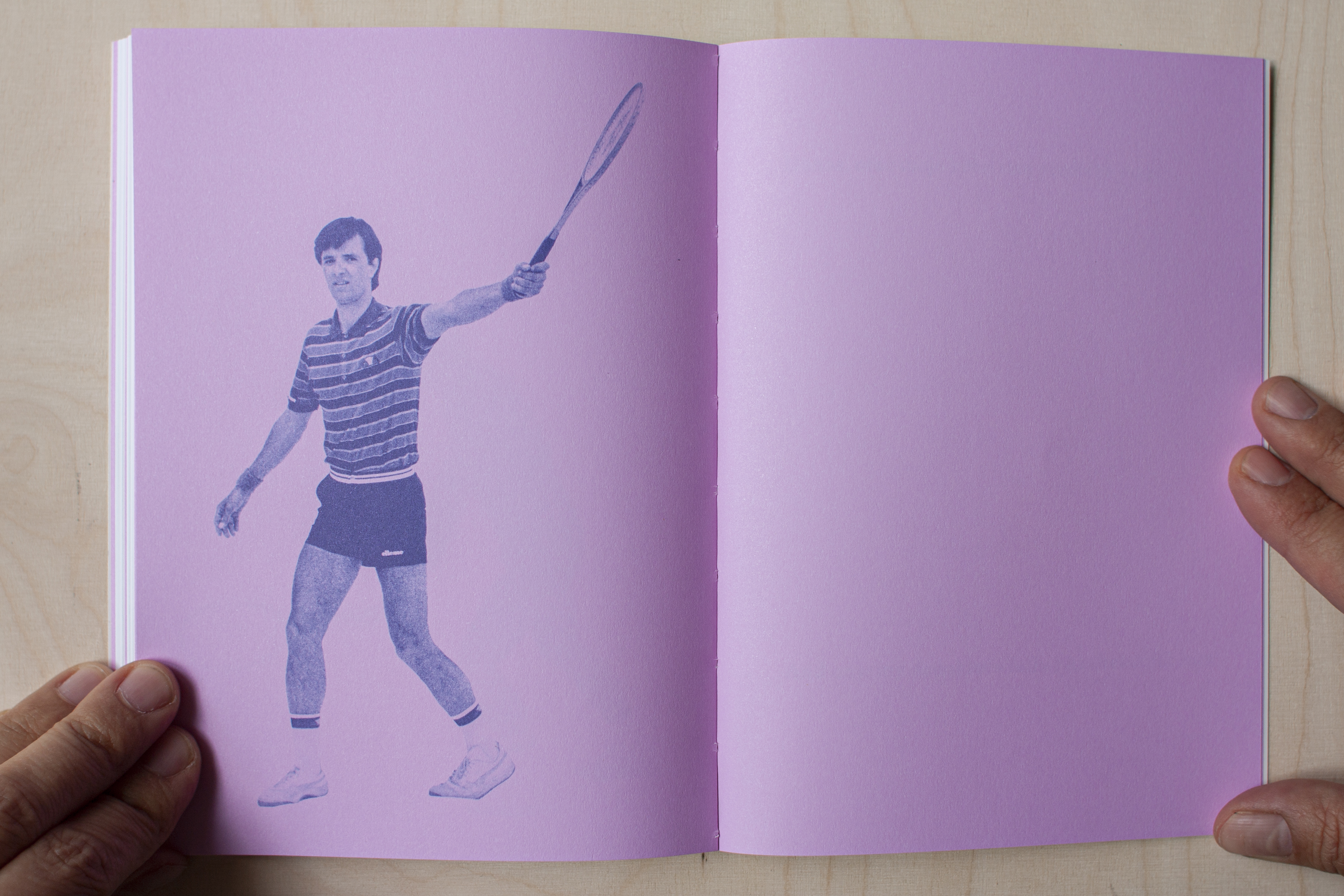

SP: First of all, I have to say this was the first time I was working on a researched topic. Normally, I’m photographing my everyday life as part of my obsession and later, after several years, I will look back into my archives to see what was driving my attention. But this project was different: I wanted to make work about my father as a way of therapy, to understand our relationship and conflicts. When I started to analyze our relationship, I found that tennis was the connecting point between us. My father was a tennis player and coach, as was my grandfather. So searching in our family archive, I found a lot of amazing material: original pictures of tennis games, some game reports written by my father, and a tennis book. This one was a manual for left-handed tennis players, written by my grandfather and with pictures of my father inside. So I started to shoot my own imagery in response to these pictures.

My initial idea was to produce a lot of still life images with rackets and other elements that recalled tennis. Then, referring to the images of my father, I began to ask my partner to take on the same positions. And then I remembered my Mum saying this thing about my father’s legs, which she still says—“I fell in love with your father because of his beautiful legs”—and I realized the logical circle around that topic was closed, history repeating itself.

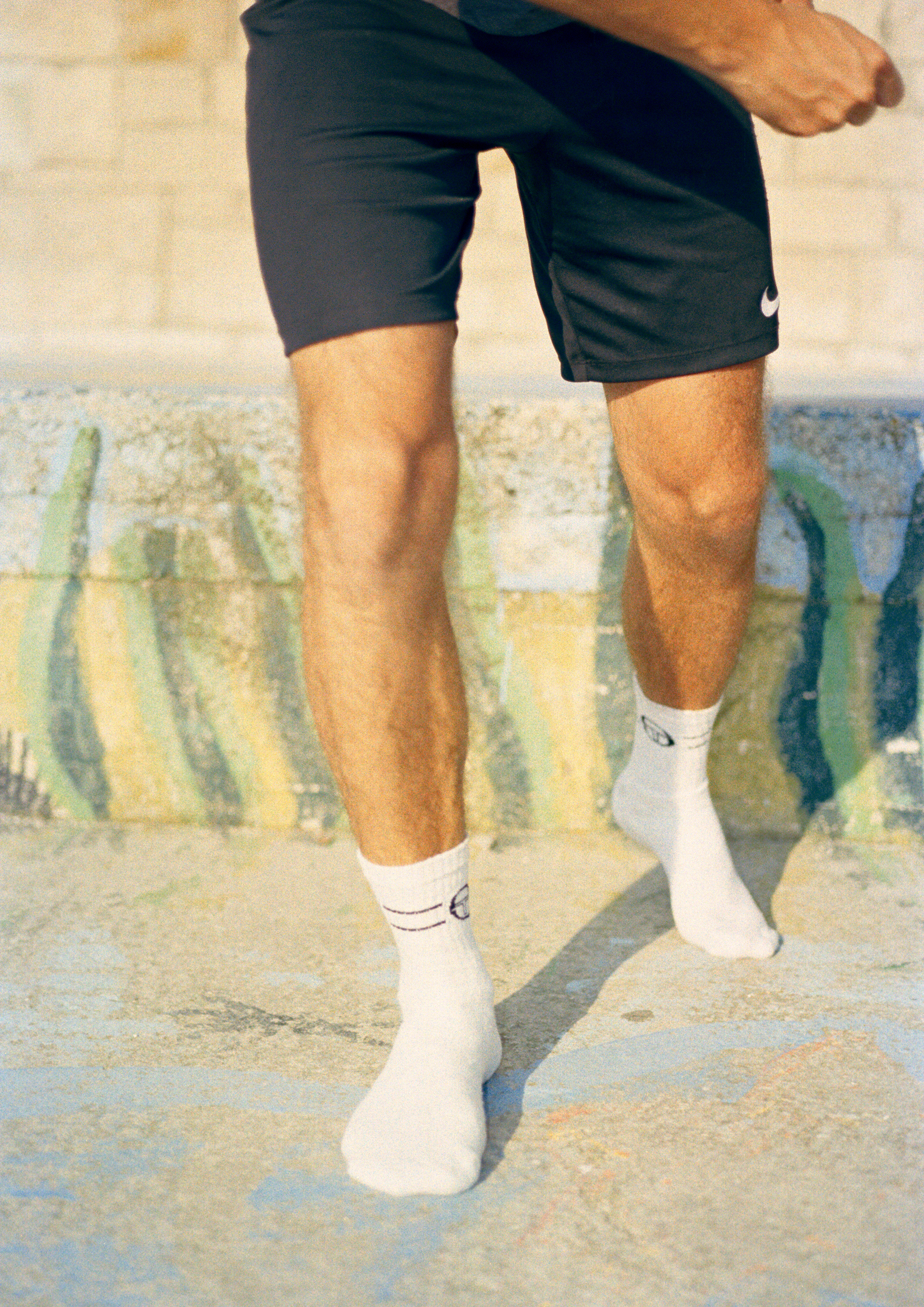

Backhand on Island, Susak, 2019

Backhand on Stairs, Pula, 2019

Service In the Hallway, Berlin, 2019

JL: The first thing I noticed about the book is how it so explicitly objectifies the male body. We never see your partner’s face or torso, only his legs. Cut off from the rest of his body, the tennis stances he performs suggest a contrapposto pose and classical ideals of athleticism and beauty. But at the same time, the photographs are also tender and personal—clearly, these are not a stranger’s legs. What role does desire play in this work? How do you place this body of work within a history of photography that has so often objectified the female body?

SP: The legs become the object of desire through their repetition. At the same time, this repetition is influenced by the role that obsession has in my work.

I think my realization of how the book objectifies the male body came after the project was done, realizing that now there is a book showing male legs, one after the other, as if it were a catalog. After centuries of objectification of the female body, my project, in its small way, overturns that point of view. But the question that I’m raising after the completion of the project is if we can use the tools of the patriarchy to dismantle it? Is it right to ‘play’ the game in the same way?

At the same time, if I would have used the whole figure instead of its part (the legs), the viewer would have been concentrated on other aspects of the body. So it was a clear decision to include only the part for the whole. And, I never saw this body of work compared to the classical ideals of athleticism and beauty, but now that you say that it seems so clear to me that it has a visual reference, and I like it!

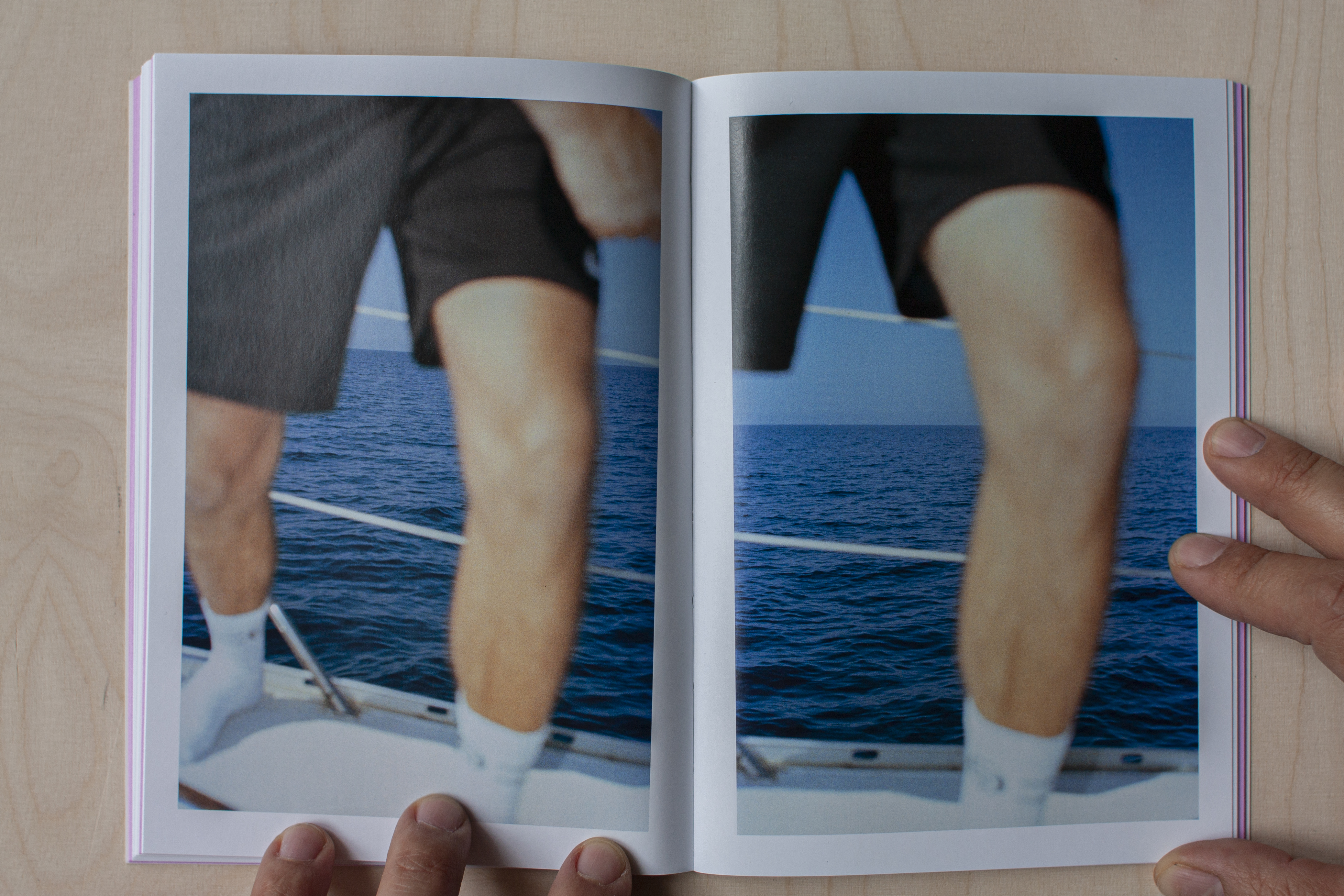

My Father’s Legs, book spreads, J&L Books, 2020

JL: Can you talk about what role obsession plays in your work, whether this project or other projects?

SP: I never thought of myself as an obsessive person, although I often had ‘waves’ of obsession at different points. For example, I started to read really late as reading initially felt too slow for me. But then as I started reading, I would read a book in several days and I was so focused on finishing that book that I would ignore any social life during that time. And now, it’s a similar sort of thing with photography: after months of shooting, I begin to see some patterns repeating. Then I tend to recognise them and put my effort more on those topics. And that’s how my obsession starts (or was it already there?). The problem is how to finish, which I still don’t know. My obsession with photographing palms finished by publishing the work, but the legs obsession remains even after I published it. But, overall, I think that obsession is the main trigger of my work.

Service Position in Elsa’s Room, Berlin, 2019

JL: The locations of the photographs in My Father’s Legs are ambiguous. Often, it appears as a domestic space, indicated by floral drapes, the plush purple carpet of a child’s room, perhaps a lace tablecloth in the background. At one point, vinyl flooring suggests a gym, while in a few other images it is clear he is on a boat or outside. It makes me wonder how these photographs were made. Where were you making these pictures and was that significant? And, what did the collaboration between you and your partner look like?

SP: For me it was the first time I made staged images. I was not looking for particular shots, but obviously, I direct my partner to position himself. I acted as a director and it felt really strange, even more so if we think of it as me, a woman, directing my partner, a man. It felt like taking over power.

The first shots happened in our bedroom, in front of the curtains, because I wanted the photograph to have a theatrical but at the same time neutral background. But it was also a practical issue, because it was the only place we could both be at the same time since our daughter was sleeping in the next room. So, we had to be inventive.

Sometimes, I would stop him while he was doing other stuff, pick up my camera and ask him to pose in a particular position: this happened once in the kitchen while he was cooking, or once as we were sailing through Croatian Islands where we would run early in the morning and make some photographs before leaving again.

He was often staying in balance on different surfaces for a long time while I was moving around him to find a good shot, and other times he was moving so fast from one position to the other, almost dancing. It was fun!

JL: Bookmaking seems to be an important part of your practice. Can you talk about the process of designing and producing this book with Jason Fulford? How much were you thinking about the role of humor when you produced the book?

SP: I first met Jason Fulford at a portfolio review at ISSP Summer School in Latvia in 2018 and he recognised the potential of the legs immediately, which was a huge blessing for me. Jason came up with the design idea, which we then discussed together and improved a bit. But if you see the first draft and the last one, they’re almost the same.

The humor came almost at the beginning: after one year of producing the work, I felt like it was going in a too serious direction. I didn’t want to make a heavy body of work about the relationship between father and daughter. So the legs became a funny, lighthearted way of talking about it.

from the series WOMB, 2020

JL: You are also an architect. Do you find that influences your photographic practice?

SP: Maybe it did a few years ago, as architecture is something that shaped me for such a long time. But now I think it is more the other way around: photography shapes my way of dealing with space and combination of objects in architecture. I recently found this in a book: “Modern architecture works through analogy, symbol and image . . . We look backward at history and tradition to go forward . . .” So if we read architecture like this, then perhaps, I can say, yes, it has influenced my photographic work.

from the series WOMB, 2020 (above)

First Breakfast, 2014 (right)

JL: What are you working on now?

SP: I’m currently working on a reinterpretation of some spreads of my grandfather’s book ‘Igrajmo tenis’ (Let’s Play Tennis) in risoprint. The second thing I’m working on right now is my project WOMB (working title), which is one of my long-term, ongoing projects. It is a collection of feelings, states of mind, individuals and objects, a back-and-forth between emotion and abstraction. It is a reflection and mirroring of my experience as a woman—floating in constant search of who I am and how I feel. It is a state of constant self-therapy, a fluent narration through visual metaphors about the changes that occur while I was becoming a mother.

JL: Prior to My Father’s Legs, you produced several other small-run publications, including Palmeral, a riso-printed photo book of tropical plants, and aTree zine, a free magazine you produced in collaboration with various young photographers, each created with a single sheet of A3 paper. What is the thread of inquiry that holds all these projects together for you? What are the themes that you find yourself returning to as an artist?

SP: I think for sure I keep returning to printed matter and the playfulness of its forms. But also, both of the projects—aTree and Palmeral—came out in a moment when I was bored as hell and my brain started to be extremely productive. So instead of finishing my last boring exam for school, I produced aTree with the focus of bringing some fresh imagery to the inhabitants of my hometown, Pula, Croatia. Palmeral, on the other hand, started with the long obsession I’ve had with palm trees. I love their structure, or maybe their architecture—the leaves and the playfulness between light and shadows.

from the series WOMB, 2020

JL: What have you been turning to recently for inspiration?

SP: I’m reading John Berger’s Ways of Seeing parallel to a selection of short stories by Lydia Davis, as well as Orlando by Virginia Woolf. I found a really beautiful second hand bookstore, Hopscotch Reading Room, in Berlin, which has introduced me to a lot of short story writers. I think this is my biggest discovery of late and I’m enjoying them a lot, finding in these short stories new inspiration for my work.

I'm convinced that what we photograph is shaped by what we see, by all the visual input we receive, and at the same time we're always searching for something familiar that we already saw. So, in the end, I think that what inspires me and what I’ve researched as inspiration is how we depend on each other.

JL: Thanks so much for your time, Sara. For more information about Sara Perovic’s work, publications, and exhibitions, visit her website: www.saraperovic.com.