An Interview with Sarah Meadows

March 2, 2023

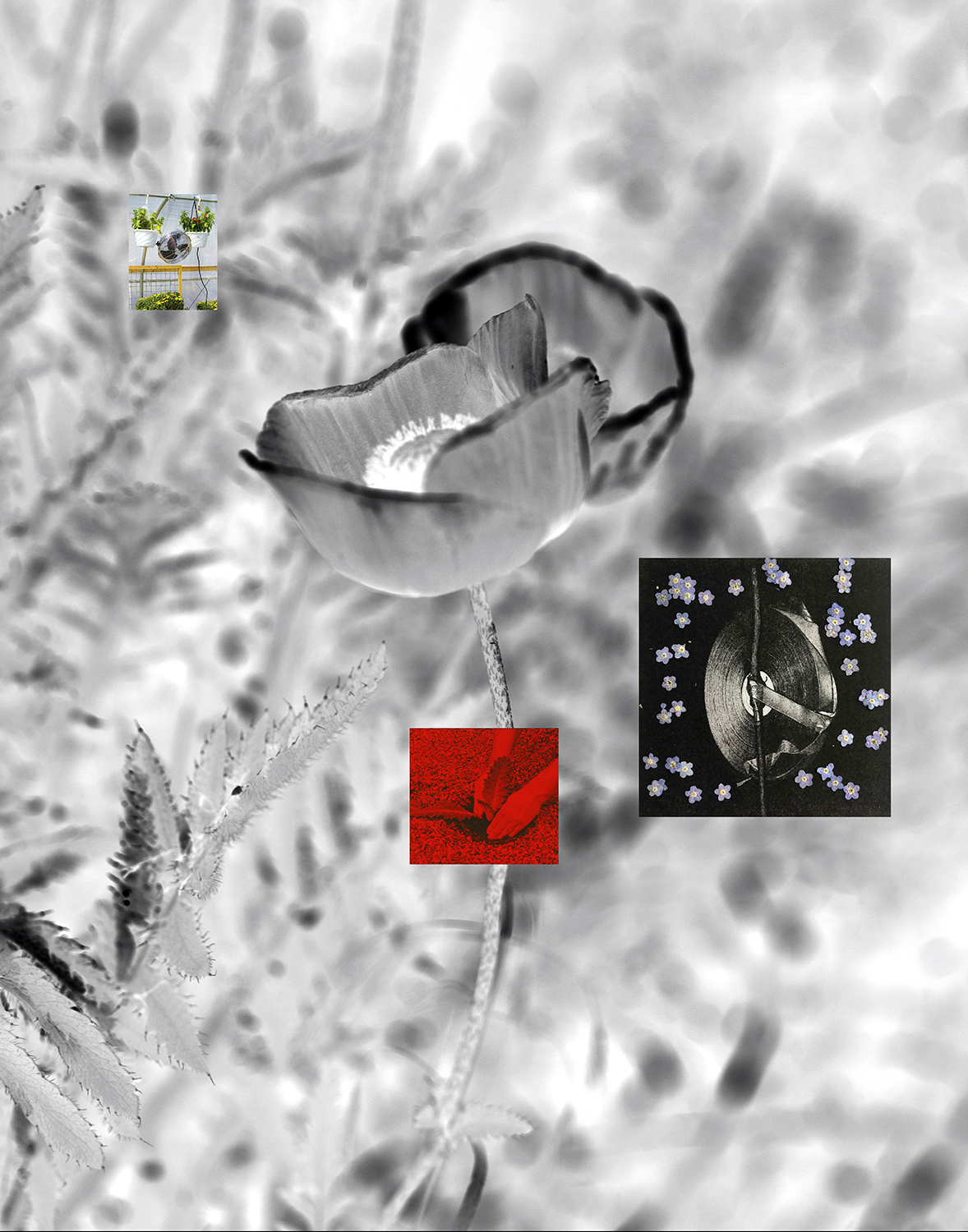

Though often spare in themselves, Sarah Meadows’ photographs and sculptural objects speak to the saturation of images and an uneasy relationship to the natural world that is more often than not mediated to us through devices and screens. In Meadows’ work, photographs of fruit and flowers – plums wet with dew, poppies, forget-me-nots – transform into uncanny collages, incongruent colors, and glitched files.

“Putting photographs together feels, to me, like posing a question,” writes Meadows. Using found images (mostly sourced from the internet and Youtube, often from gardening guides) in addition to her own photographs, Meadows string images together into visual poems where nature is presented as something to be seen. In this world of images, we are not part of the natural world, but rather seduced by it and separate from it. The question Meadows poses is not so much about nature but rather how we experience it, as something to control, desire or fear.

Meadows received her MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2016 and her BFA in Photography from Pacific Northwest College of Art in 2008. She also holds a BA from the Evergreen State College and has studied internationally at the Glasgow School of Art. Her work is published by Publication Studio and the Institute for Interspecies Art & Relations.

—Jessina Leonard

Medicated Corrugated, Archival Pigment Print, Laser Print, and Yellow Tinted Adhesive Film, 11.5 in. x 15 in., 2018

A Hardy, Twining Climber, Archival Pigment Print, 40 in. x 50 in., 2016

JL: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me, Sarah. Your work explores how nature is imagined through photography. Where did your fascination with this topic begin?

SM: It began in childhood – I’m an only child and spent a lot of time outdoors or reading books about animals and outdoor adventures. I also had parents who liked doing things like hiking and gardening, so it was a part of our life, in general, to be in nature often. As a kid, the media that captured me was stuff like Ranger Rick magazine, Snow White, Bambi, and books like Peter Rabbit and (later) My Side of the Mountain. It's an interest that’s been with me for so long, it’s difficult to pick out where it started or why it feels so potent. Nature has always felt like a fantasy space for me, where everything is possible. I see a separation between “real” nature, which is sometimes nice/beautiful/interesting but also brutal/dull/grotesque, and fantasy nature. I’m interested in that tension between expectations and reality and exploring the larger history of the Western and American cultural relationship to the non-human.

JL: You have written elsewhere that, for you, making photographs serves as a control against anxiety – perhaps, in particular, the increasing instability we face amidst climate change. I can’t help but think that images can also be a source of anxiety at the same time, through the limitless interactions we have with photographs on a daily basis. What is it about the practice of making images that assuages this anxiety for you?

SM: To be clear, I don’t know if it’s necessarily working that well! Looking at and making pictures is often a self-soothing activity for me, but generally, I have persistent anxiety nonetheless. Making or seeing a beautiful image is very pacifying to me – either one allows me to lose time and lose myself a bit, to take a short break from the loop of my irritating ego. Sometimes I can fuse that anxiety or fear into the work, but it usually appears as a deeper subtext, a sub-sub-subtext. Image culture is something I find both very attractive and very tiring. It doesn’t always feel good or healthy to be inundated with images en masse every day, but it is fascinating.

Breath of a Greenhouse Fan, Archival Pigment Print, Laser Prints, Dried Forget- Me-Nots, 30 in. x 36 in., 2018

JL: How has your relationship to making art shifted in the past five years amidst the unprecedented impact of climate change? I am thinking of this especially in relation to where you currently live in the Pacific Northwest and the recent extreme heat and fires that have ravaged an area that many people had believed would be a safe haven from the climate crisis.

SM: It definitely is affecting how I approach the work, and I’m not sure how that will manifest. I don’t feel like I know how to express this kind of grief and anger coherently or usefully. The Pacific Northwest is where I grew up and has always been a mild place: few extreme temperatures, relatively uncrowded, pretty pleasant all around. A few years ago there was a period when the temperatures were over 110 degrees, and it really scared me. Wildfires are a common thing towards the end of summer and turn the air into a wall of smoke, and the nature spots I grew up going to are much more crowded and trashed than they used to be. But, it’s such a privilege to live somewhere beautiful. These issues feel slightly less critical when I compare them to other things happening in the world. I don't think that I'm trying to infuse an explicit message or argument about climate change into my work – for me, that's something to address through community, action, and education. Fear and concern are part of my impulse but they also drive me to reflect on my idealistic views of nature and the insidious ways that our culture treats it as a product to be consumed.

JL: In your bodies of work, Tendings the fragrant hordes and If but a sunbeam strikes too warm, you manipulate your own photographs of the natural world, as well as images you have appropriated from the internet. You also often bring together multiple images in the same frame, whether physically or as a digital collage. Can you talk about why the juxtaposition or layering of these images is important to you?

SM: It relates to my experience of contemporary image culture. The high volume of information and stimulation feels like a defining element of this blip in the historical timeline. Have we ever had so much to look at?! I’m curious about capitalism's “functional” images that are essentially authorless and disposable and how they may contain beauty, humor, etc. The sliding scale from a fine art landscape to a newsprint coupon for a strawberry is fascinating to me, and the specific language of each of those photographs is enriched and complicated by juxtaposition. Putting photographs together feels, to me, like posing a question. Not necessarily a direct comparison, but a question about how they might be related (historically, emotionally, aesthetically) or how it feels to look at them simultaneously. I also sometimes find my own pictures lacking or disappointing and add other elements to make them feel complete or connect them to the broader world of nature imagery I'm engaged with. Maybe it goes back to anxiety, feeling a need to pack more stuff into the work because I’m afraid it’s not enough.

AMPAMOMP, Perfect Bound Book, Risograph and Laser Print, 3.5 in. x 5.5 in., 2019

JL: Your book, AMPAMOMP, is a collection of text appropriated from YouTube comments on instructional gardening videos. Taken out of context, these short poems draw from the banal and sentimental – “I want to marry gardener one day” – to the anxiety and fear inspired by nature – “everything I touch dies” or “So much fruit seems wasted.” What were you looking for when you assembled these texts?

SM: Initially, I was gathering without a specific plan. A lot of my practice starts with just looking and following my intuition. I was at a residency in Maine and had the free time to pick at a loose thread, which was a growing obsession with gardening videos on Youtube. I started with transcribing some of the dialogue but shifted focus after I scrolled through some of the comment sections. The emotional quality of the writing struck me. It all revolved around control – the dream of a garden as a romantic, perfect space that’s perfect and impervious to pests and outsiders and produces beauty. Some of these people were avid gardeners themselves, some very clearly not. As with many places on the internet, the YouTube comment box is a low-stakes, anonymous place to offer reflections. I started to copy particularly expressive comments into a new document and brought it to a get-together with the other residents where we would each reach something to the group. We laughed a lot, had a great conversation about how it felt like poetry, and I started the layout the next morning. The book probably wouldn’t exist without that place/day/group of people and my friend Aidan at IFIAAR who decided to produce it. My role was as an editor, extracting and rearranging to create the most potent version of the material I'd found. The language of the internet moves me in its informality, looseness, functional nature, and obscured relationship to the author and I wanted to capture that spirit.

Perennial Beauties, Archival Pigment Print, Laser Print, Found Image, and Bird Scare Tape, 2018

JL: Can you tell us more about your series, How to Draw a Bunny?

SM: I love rabbits. I have a collection of unsuccessful photos of rabbits that I’ve taken that are super blurry, distant, dark, etc. I will always take an animal or bird picture, even if I know it won’t turn out, because the gesture feels so right and so dumb. I saw you, and I have proof. It’s propelled by a desire for connections that are not really possible or in the best interest of the animal.

These images were appropriated, and sourcing them started simply with a desire to see a bunny that day. I was thinking about a rabbit running away from observation, trying to exit the picture as quickly as possible. They were small jpegs that I printed as large black and white laser prints (30 x 40”) on thin paper, bad prints in terms of photography. The lack of sharpness and color, the digital noise, and the fragility and cheapness of the material are important – I have these images on my website at the moment, but that physical print is where the meaning lives. For as much as I love to explore the digital world, I tend to make things that are very tactile and materially-oriented.

JL: What are you working on these days?

SM: I wrapped up an exhibition at the end of summer and I’m mostly sorting through all of the experiments and test pieces that didn’t make it into that show. There are anthotypes and contact prints, drawings made with flower essences and bee pollen, collages, and a ton of film scans, all needing more editing and attention. I’m also working on a book of the found image collection I’ve maintained since 2004. Focusing specifically on digital images of nature I found online through years of searches, it pulls from obvious sources, like cute animal culture, as well as from scientific and instructional websites, online shopping sites, travel guides and tourism, animated gifs, agricultural guides, tools for land use, and historical research. So far it’s a sprawling mess, but I’m enjoying the process of loosely organizing images by color, subject, size/resolution, etc, and looking for sequential combinations.

JL: Thanks so much for your time, Sarah. For more information about Sarah Meadows’s work, publications, and exhibitions, visit her website: www.sarah-meadows.com.

Love in Idleness, Archival Pigment Print, Garden Netting, Bird Scare Discs, Laser Print, Gouache, 20 in. x 34 in., 2018